By Lauren Audi

One of my most prized possessions is a 1st edition, fourth impression copy of A Room of One’s Own by Virginia Woolf published by her company, Hogarth Press. It isn’t worth a lot of money, nor is it in great condition, but that doesn’t matter. It is the knowledge that this text about how women need space, time and money to pursue their passions was not only written, but actually made by Woolf, imprints the object with an inexpressible sense of meaning.

These are the types of items – works by and made by women – found in a single room in midtown Manhattan. Such feminist relics were carefully scavenged for over half a century by one woman, Lisa Unger Baskin. Among such treasures is a cabinet card of Sojourner Truth, the revolutionary feminist and abolitionist born into slavery here in New York State. Below the silvery portrait she sold to support herself are her own heart-rendering words, “I Sell the Shadow to Support the Substance.” These words reverberate throughout the exhibition, seeping into the lives and stories of the women who worked diligently and painstakingly to support themselves in a world stacked against them.

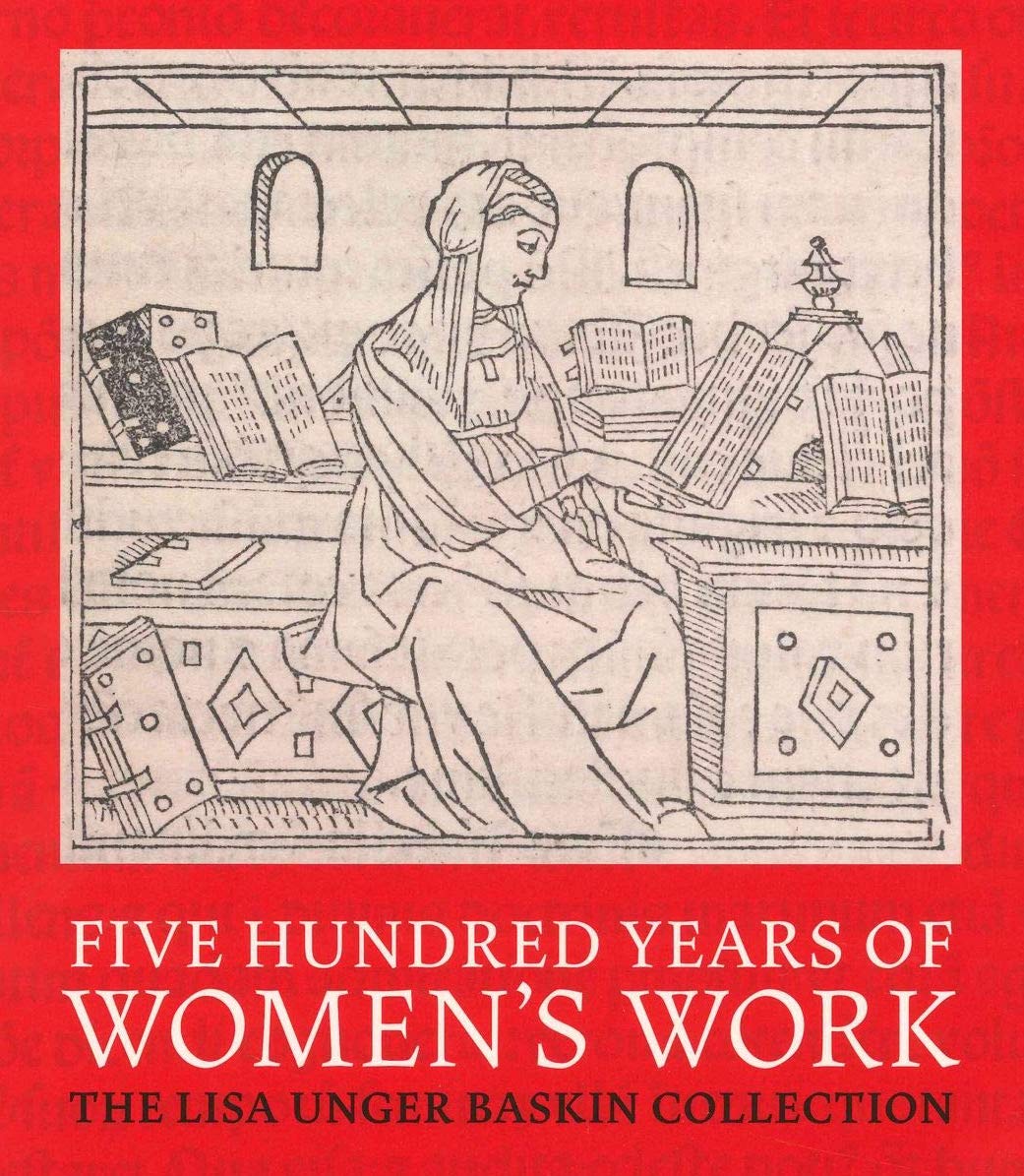

“Five Hundred Years of Women’s Work: The Lisa Unger Baskin Collection” is on exhibit at the Groiler Club in Manhattan. This literal “Room of One’s Own” is the lifework of collector, activist and bibliophile, Lisa Unger Baskin. As I wandered the carefully curated cases, arranged by century, I am affected by the heavy reality of just how much of women’s history has been forgotten, lost, or simply ignored. Museums and institutions are still largely bereft of women’s works, often delegating them to special exhibitions rather than permanent collections. A 2018 study led by Chad Topaz of Williams College found that 87% of artists featured in major permanent collections were men. While collections show obvious gender inequality, there has yet to be a meaningful shift toward inclusivity. A survey by Artnet and the “In Other Words” podcast found that only 11% of all work acquired by the country’s top museums in the past decade were by women.

The women showcased here did traditional “Women’s Work” such as domestic duties and occupations like teaching, nursing, or housekeeping. However, the exhibit upends stereotypes of such women and their lives, casting them into the profound and meaningful, rather than subjecting them to the ordinary. There is an old proverb you have probably heard. It goes, “A woman’s work is never done.” Yes, these women raised children, cleaned houses, cared for relatives, worked as nurses and teachers, but at the same time they wrote books, provided women’s healthcare, made art, contributed to science and literature all in a world that denied them basic rights to property, ownership, voting and banned them from making a living in most fields.

Many of these women pursued their passions at great costs to themselves, dying unknown and in poverty. 19th Century New York abortionist, Anna Trow Lohman, known as Madam Restell, sold patent medicines for birth control and abortions. Her husband published medical companions on such topics under a pseudonym. Restell was arrested in 1878 for the distribution of “obscene literature,” but before she could face charges, she committed suicide. Martha Maxwell, a pioneering naturalist and taxidermist, struggled her whole life to find a place in the scientific world. She was perhaps the first woman to hunt and prepare animal specimens that were exhibited at museums. She is also credited as being the first person to display taxidermy in their natural settings, a practice that is now common at natural history museums all over the world, including the one I work at – The American Museum of Natural History. However, Maxwell struggled to obtain rights to souvenir photographs from her exhibitions and died in poverty. Another book in the collection tells the story of a black woman, Ann Williams, who, to avoid capture by slavers, jumped from a window breaking her back and leg. Afterwards she successfully petitioned for the freedom of herself and her children. The print in the book depicting her jump is a harrowing reminder of the adversity and suffering black Americans and specifically black women in America have had to fight against to achieve the most basic of freedoms.

These remarkable achievements and many others would still remain unknown if it were not for one woman, Lisa Unger Baskin, who has made it her life’s work to preserve and remember these histories. Baskin was born a collector. As a child her parents cleared out a closet and added floor to ceiling shelves to house her continually growing book collection – her first library. Even then, she was drawn to books by women. However, it was in the 1960s that her collecting began to develop a strong sense of purpose – recovering, preserving and remembering the diversity and depth of women’s work throughout history, however “ordinary”. In the 60s, few had yet begun this mission with such dedication. She would often stumble across incredible works in flea markets and estate sales, purchasing the items for mere dollars. . She recalls one time at a flea market in Manhattan where she was randomly handed a box of items “relating to women.” Within it, she found preparatory material for Adelaide Johnson’s sculptures of Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott that were to be displayed in the Rotunda of the United States Capitol in 1920 after the 19th Amendment was ratified.

Baskin’s collection has since grown to over 16,000 items including books, manuscripts and artifacts. In 2015, she placed her collection at the Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture at Duke University. She came to the decision after a particularly harsh storm threatened the Massachusetts farmhouse where she had been storing the items, forcing her to face the reality that the objects could be lost again, this time forever.

The oldest exhibit dates back to 1240 with a land grant in Pisa, Italy for a home for repentant prostitutes. It also includes one of the first books known to have been printed by women. In 1478, the nuns at the Convent of San Jacopo de Ripoli in Tuscany set type, sewed folios, and provided financial backing for the press. The book is open to an entry with manuscript additions likely scribbled by the nuns including one about, “papa femina” or Female Pope, referring to the mythical religious figure, Pope Jean. The most recent items include publications by the 20th Century anarchist Emma Goldman and a political poster of lawyer and activist Inez Milholland Boissevain. Between these two bookmarks are items including a 1592 book with woodcuts made by artist, Geronima Parasole, a 1630 letter by famous artist Artemisia Gentileschi, a 1707 book of observations by midwife Lousie Bourgeois Boursier, a 1773 first edition of the first book published by an African American, Phillis Wheatley (Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral), and 1893 copy of The Reason Why the Colored American is Not in the World’s Columbian Exposition by pioneering black journalist Ida B. Wells.

Baskin’s collection, although focused on American and European history, attempts to be inclusive of race and sexuality. However, by her own admission, she falls short due to her own language barrier when it comes to representation of Asian women. Black writers, artists and abolitionists are prominent in the exhibition, showcasing how inextricable black women have been in pioneering opportunity, pathways and rights for women of all color while simultaneously remaining one of the most vulnerable groups in the world. Baskin notes that the Seneca Falls meeting was in fact not the first women’s rights convention, but prior to that, in 1837, there was a female anti-slavery convention held and attended by both black and white women. The night before the second meeting the location was burnt down by angry protesters.

A remarkable part of queer history is also included in the exhibition. A creamer and figurine depict the Ladies of Llagollen, who were late eighteenth century aristocrats Eleanor Butler and Sarah Ponsonby. These two women abandoned their lives in Ireland to be together, moving to Wales, and understood themselves to be married, though same-sex marriage was not recognized by the government until 2014. They became important figures in the 19th century queer culture.

I attended the exhibition with the American Museum of Natural History’s Women in Natural Science group. Baskin herself gave the tour of the collection to a room crammed full of visitors, impressing her passion and encyclopedic knowledge of the histories. As an employee of one of the oldest museums in the United States, I often think about how underrepresented people are included – or not included in museums and institutions. Baskin’s collection shows us we still have a lot to do to get there – and it won’t be easy work. Her collection is interdisciplinary, it looks at women’s work from all angles – women who write, publish, stitch, draw, build, sew, teach, study, care for and protest. I left the exhibit feeling overwhelmed by the weight of the women who have come before me, pride in what they have accomplished, a yearning for all that is still lost, but mostly I felt empowered.

Baskin’s collection shows us the substance of these women too long relegated to the shadows, uplifting them to a place they have long deserved. In doing so she uplifts all of us — women seeking to pursue their life’s work, whatever it may be, with courage.