In Southeast Asia there exists a flower so exotic and strange it has captured the attention of scientists, artists and nature lovers alike. Measuring over 29 inches in diameter, weighing around 22 lbs and having no stems, roots or leaves, the genus Rafflesia, also known as the corpse flower (not to be confused with the Titan arum), is a wonder of nature. A cartoonish-ly large plant, it parasitizes a vine (Tetrastigma) in order to survive and reeks of rotten flesh, a scent particularly attractive to its pollinators — the carrion fly (Calliphoridae family).1 It is found only in Southeast Asia, and is exactly the sort of flower one imagines a tropical botanist studies. Dr. Aida Shafreena Ahmad Puad, a Professor of Molecular Plant Systematics and Deputy Dean of Faculty at the Universiti Malaysia Sarawak studies exactly the opposite.

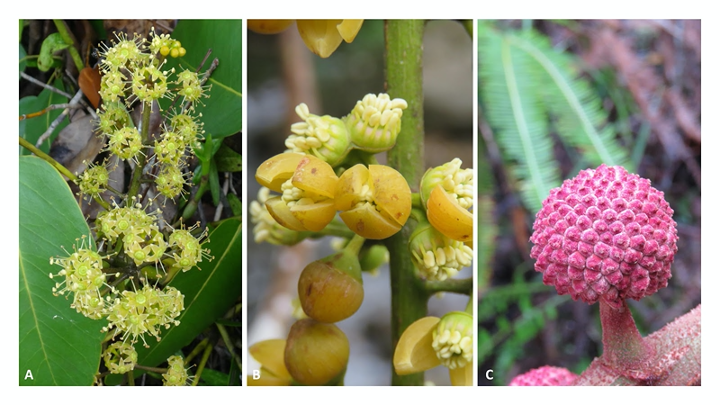

Dr. Ahmad Puad has devoted her career to studying the plants nobody else cares about. The boring, commonplace, unattractive plants that make up the majority of tropical rainforests — greens awash in a sea of green. When funding requires her to work on Rafflesia, she prefers to study the modest vine it parasitizes as opposed to Rafflesia itself. Of particular interest to her is the genus Schefflera. An estimated 600-800 species of trees, shrubs and lianas with a large pan-tropical range make up this genus.2 Despite their ubiquitous presence in the tropics, little is known about their ecology, biology, and evolution. These plants are neither brightly colored nor are they charismatic. They have no known economic importance and, in many cases, don’t even have names. Yet, Dr. Ahmad Puad can hardly contain her passion for these overlooked plants. With irony, she exclaims, “I mean how unattractive can they be? The petals fall off as soon as they open! I couldn’t have picked a blander group than Schefflera!”

The lack of understanding about this family is exactly what excites her. With so many species still to be discovered, Dr. Ahmad Puad often finds herself in awe of how many species are left to still be discovered. ” In 2018 she published, The Genus Schefflera in Sabah, Malaysian Borneo, a book describing 32 species of Schefflera from Malaysia.3 Prior to this work only seven species of Schefflera from Sabah had published names, and no new species had been described for over 100 years. Dr. Ahmad Puad explains, “there is still so much to be known, but it all begins with a name. First, we give them names and once they have names, we can begin working on some of the bigger questions of ecology.” On this front, there is still much work to be done. She plans to continue describing Schefflera species in Borneo, assuming the responsibilities of her long-time collaborator, the late Dr. David Frodin.

Like many of the women who have come before, Dr. Ahmad Puad juggles many demanding roles. She is a teacher, a research scientist, an administrator, a mother, and a mentor. “My struggle is real,” she says of the challenges she has faced. In academia, the job market is competitive and there is continuous pressure to publish new research. This often disadvantages women who want to have families. Dr. Ahmad Puad is the mother of three boys and raised them while living in a new country, the United States, and working toward her Doctorate Degree. Her passion for research keeps her going everyday.

Aida grew up in the Western Malaysian state of Perak, never dreaming of becoming a botanist. Her mother was a teacher and her father was an officer in the government. Over time her interest in the natural world grew, eventually pursuing a master’s in science from Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia. She worked on everything ranging from marine mollusks to plants in the ginger family before securing a lecturer position at the Universiti Malaysia Sarawak. She went on to receive her PhD from the Western Michigan University, spending four and a half years studying in the United States while raising a family. Despite the hurdles she encountered, Dr. Ahmad Puad hopes to see more women take on higher positions in science and leading roles in plant systematics in the near future.

It took Dr. Ahmad Puad five years to write her book, partially because of her many responsibilities, but also because the resources she needed were no longer in Borneo. “When we want to study a group of plants, we have to know what is already there and that is where the challenge begins,” explains Dr. Ahmad Puad. Botany in the tropics is deeply tied to a history of colonialism. From as early as 1511, Malaysia was continuously conquered, changing hands between various European nations.4 Explorers, under the guise of colonialism, took advantage of native people’s knowledge, resources and ecosystems, proclaiming the “discovery” of many species in the tropics that had been known for centuries. They collected thousands of specimens, retained ownership of type specimens (the particular specimen for which the scientific name is formally attached), and named them without the consent or knowledge of local people. These invaluable resources still remain in herbarium collections far from their native homes and lack detailed information about indigenous names and uses. The rules regarding botanical nomenclature require the first published name to be retained for a species.5 Unfortunately, this rule is skewed toward western conceptions of science, resulting in the loss of many indigenous names and knowledge sets.

Dr. Ahmad Puad had to travel thousands of miles to herbariums around the world, including Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, and the New York Botanic Garden just to see specimens that were removed from their native Malaysia. This was eye-opening for Dr. Ahmad Puad . Many of the credited scientists were actually businessmen who sold the specimens for profit, while the locals who served as guides and collectors were uncredited on the collection tags. In response to this realization, Dr. Ahmad Puad has made sure all of the type specimens and isotypes (a duplicate of the type specimen that can be used for reference) collected for her research stay in Malaysia. Additionally, she makes it a point to include her entire team in the success of her research– from students to park rangers to local guides. “It is not just the scientist, but the people behind the scientist that make the research possible,” says Dr. Ahmad Puad.

Cataloguing the unknown schefflera diversity in Borneo is one part of what Dr. Ahmad Puad sees as a much larger research and conservation goal – identifying all of the biodiversity in Borneo. Borneo has long been thought of as one of the greatest biodiversity hot spots in the world, but the exact number of native species is unknown.6 As deforestation increases and the effects of climate change become increasingly drastic, more species will be lost that were never discovered in the first place. “We don’t really know what the value is,” Dr. Ahmad Puad says of the ecosystems. “It’s like we are being robbed and we don’t even know how much we have lost.” Schefflera, unlike charismatic Rafflesia, does not readily receive thousands of dollars in funding and support. The genus is much harder to study given its taxonomy, expansive range and lack of scholarship. However, for this very reason it is important to study. Her goal, then, in researching an unappreciated genus, is not only to bring new information to the field, but also to identify the value of something we didn’t even know we had and may not even know we are losing.

Authored by: Lauren Audi

References

- Zakaria, W., Fatiha, W. N., Puad, A.A.S., Geri, C., Zainudin, R., & Latiff, A. (2016). Tetrastigma diepenhorstii (Miq.) Latiff (Vitaceae), a new host of Rafflesia tuan-mudae Becc.(Rafflesiaceae) in Borneo. Journal of Botany, 2016.

- Puad, A.A.S.. (2012). Preliminary Revision, Phylogenetics and and Studies of Leaf Anatomical Variation Along an Elevational Gradient in the Genus Schefflera (Araliaceae) in Sabah, Malaysia.

- Puad, A.A.S., Frodin, D. G., & Barkman, T. J. (2018). The genus Schefflera in Sabah, Malaysian Borneo. Sarawak: UNIMAS Publisher.

- Lach, D. F. (1994). Asia in the Making of Europe, Volume I: The Century of Discovery. University of Chicago Press.

- Greuter, W., McNeill, J., Barrie, F., Burdet, H. M., Demoulin, V., Filgueiras, T. S., … & Turland, N. J. (2000). International code of botanical nomenclature (Saint Louis Code): Sixteenth International Botanical Congress, St Louis, Missouri, USA, July-August 1999. In International code of botanical nomenclature (Saint Louis Code): Sixteenth International Botanical Congress, St Louis, Missouri, USA, July-August 1999.. International Association for Plant Taxonomy.

- Bryan, J. E., Shearman, P. L., Asner, G. P., Knapp, D. E., Aoro, G., & Lokes, B. (2013). Extreme differences in forest degradation in Borneo: comparing practices in Sarawak, Sabah, and Brunei. PloS one, 8(7).

Images

- Dr. Ahmad Puad in Kalamazoo, Michigan where she completed her PhD at the University of Michigan. Photo Credit: Chong Leling, 2010.

- Rafflesia Arnoldii, also known as stinking corpse lily, produces the largest individual flower of any living species. It is endemic to Sumatra and Borneo. Photo Credit: Maizal Chaniago, 2018, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Rafflesia_Arnoldii_Batang_Palupuah_Indonesi

- A selection of Schefflera inflorescences described by Dr. Ahmad Puad in her recent book. A. Schefflera littoralis B. Schefflera mitragera C. Schefflera lanata. Photo credit: A- Mohamed Abdul Majid, B-C – TJ Barkman

- Dr. Ahmad Puad examining Schefflera specimens at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew in London England. Photo Credit: Dr. Ahmad Puad, 2010.

- Dr. Ahmad Puad botanizing with her students near Waras Hut (~3200m) on Mount Kinabalu in Borneo. Photo Credit: Siti Sobrina, 2013.