Alice Eastwood collecting plant specimens in the field, while holding her wooden plant press

Childhood/Alice in Wonderland

Alice Eastwood was born on January 19, 1859 in Toronto, Canada.1,4 Her childhood was a difficult one; at age 6, she promised her dying Irish mother, Eliza Jane (Gowdey) Eastwood, that she would take care of her younger siblings, Kate (who was 2 years younger than Alice) and her baby brother Sidney.1,2,4

After her mother’s death, her father, Colin Skinner Eastwood, immediately left all three children in the care of relatives.2,4During this time, Alice Eastwood stayed with her Uncle Helliwell, who was an experimental horticulturalist in Ontario, Canada.1,2,4 He shared his passion for botany with young Alice, teaching her plant names and gifting her books about plants.2 Growing up, her two favorite wildflowers were partridge berry and wild raspberry.3Two years after her mother died, Alice and her sister moved into a convent in Oshawa, Ontario, where an elderly French priest-gardener, Father Pugh, nurtured her early botanical interest.1,2,4 Here Eastwood also learned about music from a French Canadian nun2; later in her life she was able to earn extra money through teaching music to a woman in a nearby village.4

In 1873 at age 14, Eastwood joined her father in Denver, Colorado.1,2 There, she helped with family expenses by working as a nursemaid taking care of the young children of the Scherrer family.2 This association proved fortuitous, as the Scherrers had a comprehensive multilingual library and asked her to regularly join them on camping trips in the Colorado mountains.2 On these trips Eastwood marvelled at the Alpine vegetation; she had never encountered such diversity of plant life before.4

A local teacher and musician, Anna Palmer, tutored Eastwood, enabling her to enter high school.2 However, when her father’s grocery store lost money, Eastwood was forced to drop out of school and return to work.1,2Despite this setback, her strong work ethic prevailed. Eastwood took on multiple jobs, waking at 4am to attend to the furnace in the school building, and working as a cutter’s assistant in the dress department of a downtown store.2 Eastwood managed to pay all her own expenses through her hard-work, bringing in enough money to support her family and returning to East Denver High School as a senior, where she graduated early.2

Eastwood was elected class valedictorian of her high school after years of overcoming difficult situations.2Her valedictory address was published in the Denver Tribune.4She received two books as graduation gifts, Porter and Coulter’s Synopsis of the Flora of Colorado (1874) and Gray’s Manual of the botany of the northern United States (1878).4 Eastwood became a high school teacher instructing students in Latin, natural science, drawing and composition, and American literature for over a decade from 1879 to 1890.1,4 While working she was able to save up her salary of $475 a year to fund her summer botanical explorations in the Rocky Mountains.4

Early Expeditions and Guiding

During her first summer after high school graduation, Eastwood learned to ride horses so that she could pursue botany in more inaccessible places.2 She also designed her own outfits appropriate for these expeditions, fashioning buttoned-down skirts made from heavy denim nightgowns.2 She traveled with minimal gear, as a tradeoff to allow her to gather specimens in heavy wooden plant presses.2

The 1880s were frontier times, and despite days upon days alone collecting and exploring on foot or horseback she never carried a gun, feeling it was a sign of fear (although the cowboys, miners, and ranchers she met along the way probably did.)2,3 Eastwood said, “Never in all my experiences have I had the slightest discourtesy and I have never had any fear. I believe that fear brings danger.” 2 On her many trips in the rugged mountain terrain, she held her own, not showing fear in the field while exploring the flora and fauna by herself, getting skilled at botany, geography and geology, and interacting with the farmers, ranchers, and other settlers of the area.2,4

In May of 1887, Eastwood, then aged 28, guided 66-year old Alfred Russel Wallace, the famous British naturalist and pioneer in evolutionary biology, up Gray’s Peak on a botanical collecting trip for three days.1,2,3,4 He was impressed by her botanical knowledge and skills in the field.4He referred to this in his autobiography My Life.4 By this time of her life, Eastwood had established herself as a botanist and had organized the only plant collection in Colorado: Colorado University’s herbarium at Boulder.1,4

Career and the Academy

In 1890, Eastwood quit teaching.1 Thanks to successful investments in real estate in Denver, she was able to dedicate herself full-time to the study of botany.2,4Two years later, Eastwood began working at the California Academy of Sciences on Market Street in San Francisco, after being asked to contribute articles by husband and wife botanical researchers,Townshend Stith ‘T.S.’ Brandegee and Katharine ‘Kate’ Brandegee, there.1,2,4

Kate was in charge of the herbarium. In the October 1890 issue of Zoe, a nature journal of the Brandegees’, an essay by Eastwood appeared, titled “Mariposa Lilies of Colorado.” 1,2An excerpt from this particular essay, written in San Francisco, displays her passionate writing and love for Colorado and botany:

“So distinct, so individual are those blossoms that they seem to have souls. They speak a wonderfully enticing language to draw the wandering insects to their honeyed depths…The bands of color on both divisions of the perianth are bewildering, impossible to describe; but more than aught else, they cause each flower to say proudly, with uplifted head, ‘I am myself; there is no other like me.’ ” -Alice Eastwood2

In 1892, she returned to Colorado and took trips to the desert country with her dear friend Alfred Wetherill.2,4Mesa Verde, the old civilization and now world-famous archaeological site of the native Anasazi people, was located on the Wetherill ranch property.2,4 She was among the first known to explore one remote area of the Great American Desert (a term used in the 1800s to describe the western part of the Great Plains east of the Rockies) and collect new specimens, some of which she named.2,4 She endured many hardships over her years of collecting with little complaint, as she viewed her work as an exciting and enjoyable adventure.2

In the summer of 1892, Eastwood was offered an invitation to join Kate Brandegee as joint curator of the California Academy; Kate offered Eastwood her entire salary by forgoing $75 a month.2 However, the existence of a romantic relationship with a companion of Eastwood’s, a journalist from the East who was living in Colorado, kept her in Colorado. Sadly, he was in poor health with tuberculosis and died before the two were able to marry.2,4

After his untimely death, Eastwood accepted the Academy position. A year later in 1893, the Brandegees retired and moved to San Diego, after which Eastwood was named the Academy’s Curator of Botany.2,3,4 She would go on to work there for over 50 years until 1949, continuing to organize and expand the Academy’s botanical collection from the Sierra and Coast mountain ranges.2

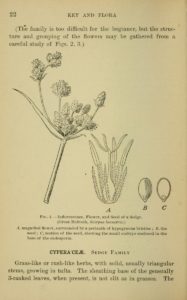

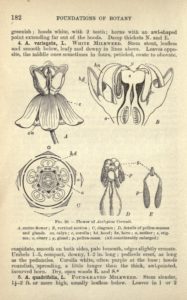

In 1901, Eastwood’s book Bergen’s Botany: Key and Flora, Pacific Coast Edition was published.1 She also published two small books, A Popular Flora of Denver, Colorado and A Handbook of the Trees of California.3

1906 San Francisco Earthquake

“My desire is to help, not to shine,” Eastwood once said.2 The 1906 San Francisco earthquake struck on April 18, 1906 and destroyed the Academy of Sciences building.1,3Here, Eastwood would both help and shine, physically saving more than 1,000 irreplaceable and most-valued plant species (1,211, to be precise3), by entering the shattered Academy building.2

She rescued the type specimens as a safeguard before fires came too close to the building; climbing the broken marble stairs as fires roared in nearby buildings. Along with a friend, she reached priceless specimens by lowering them with improvised rope, like a pulley-system, and Eastwood transported them.2

She carried the collection by hand to a safer central place, and eventually they were relocated to her home.2 Eastwood saved not only the collection, but also books from other departments and unbroken records dating back to 1853 when the Academy had its first meeting.2

She wrote a letter in the renowned journal Science discussing the 1906 earthquake, showing her spirit of accomplishment and welcoming the challenge of starting to collect all over again.3 She described, “Not a book [from my department] was I able to save, nor a single thing of my own, except my favorite lens, without which I should feel helpless.” 2

Rebuilding the Herbarium

By 1911, Eastwood traveled abroad after the earthquake and visited England, studying at Kew Gardens and the Natural History Museum at South Kensington. She observed Linnaeus’ own herbarium at the Linnaean Society in London, traveled to Paris to study Jean Baptiste Lamarck’s Herbarium, specifically the different varieties of the evening primrose, and back to Britain to study at the Lindley Herbarium.4 She finished her studies in Cambridge, Massachusetts, stopping at the New York Botanical Gardens in New York City where she met the institution’s founder Dr. Nathaniel Britton, and returned to her job as curator at the California Academy the following year to begin rebuilding the herbarium.1,4

Honors and Influence

Eastwood was one of the few women listed in American Men of Science.1 In 1926, Eastwood helped start the San Francisco Garden Club. Two years later, she was elected fellow, or honored member, of the Academy.1

In 1930, John Thomas Howell became her assistant/mentee, and later successor4, at the Academy. During their tenure together, the two of them drove through California, Arizona and New Mexico in a used Ford convertible named “Lucy,” collecting and cataloging new pressed plant specimens.1,3

She collected near the car; he ranged further afield.3 “My days of exploring on foot are over, but one can do a good deal from autos, supplemented by one’s legs,” she wrote to a friend when she was 75 years old.3 Together, Howell and Eastwood co-founded Leaflets of Western Botany, a quarterly periodical journal published in San Francisco about the American West, mostly California’s, plants.3

In 1938, Golden Gate Park received funds for an arboretum with a new Shakespeare garden, Eastwood’s idea since 1928. The creation of the arboretum was carried out by Katherina Agnes Chandler, using more than 200 plants from Shakespeare’s writings, and the garden is now used for weddings.1

In 1949, Eastwood retired as curator at age 90, after remaining at the Academy for 57 years.2 Many honors were bestowed upon her by botanists and horticulturists alike.3 Two genera were named for her: Aliciella and Eastwoodia.3

There is also a species of grass, Festica eastwoodae, named after her. She helped found the American Fuchsia Society and men of the plant nursery named a fuchsia for her, as well as a lilac and orchid.3

The Academy’s herbarium, the Alice Eastwood Herbarium, was also named after her for her pioneering action in 1893, in the Academy’s Alice Eastwood Hall of Botany.3,4 This was “my child…dearer to me than life,” as Eastwood said.3 By the end of her tenure, she had added a total of 340,000 specimens to its collection and had built up a fine botanical library with her own funds.3

Camp Alice Eastwood, a group campground, was dedicated in her honor in Mount Tamalpais State Park in 1949. The following year when she retired, she was invited to become Honorary President of the 7th International Botanical Congress.1,2 She flew to Stockholm, Sweden at age 91 and was seated in the chair of 18th century Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus, the father of modern botany and inventor of the system of naming plants and animals still used worldwide even today.1,3,4

A giant grove of redwood trees is named after Alice Eastwood, and a rare California shrub belonging to the sunflower family, Eastwoodia elegans.2,4 She was given the title “Grand Old Botanist of the Academy” by a writer.2 She also was dubbed the “gardener’s botanist.”3

Eastwood’s name is known and spoken with reverence by those close to the Academy and knowledgeable in botany.2 Robert C. Miller, of the Academy, captured her personality best describing Eastwood as “young at ninety-four because all her life she was studying, inquiring, learning, exploring…a blithe, ageless spirit living in a world of discovery forever new.” 3

Alice Eastwood died of cancer on October 30, 1953 at age 94.1,2

Authored by: Varsha Mathrani

References

- Ross, Michael Elsohn. Flower Watching with Alice Eastwood. Carolrhoda Books, Inc. Minneapolis, 1997.

- Shearer, Benjamin and Barbara Shearer. Notable Women in the Life Sciences: A Biographical Dictionary. Greenwood Press. Westport, 1996.

- Bonta, Marcia Myers. American Women Afield: Writings by Pioneering Women Naturalists. Texas A&M University Press. College Station, 1995.

- Grinstein, Louise, Carol Biermann, and Rose Rose. Women in the Biological Sciences: A Biobibliographic Sourcebook. Greenwood Press. Westport, 1997.

Additional Resources

- Eastwood, Alice. An Account and List of the Plants in the Brackenridge Journal. Journal of William Dunlop Brackenridge, California, October 1-28, 1841. California Historical Society Quarterly. Vol. XXIV, No. 4, December 1945.

- Gutzkow, F., George Chismore, Alice Eastwood. Report of the Committee to Prepare and Present an Account of the Life and Services of Dr. H.H. Behr. 1904.

- Golden Gate Park Wikipedia page: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Golden_Gate_Park\Alice Eastwood Wikipedia page: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alice_Eastwood

- Alfred Russel Wallace Wikipedia page: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alfred_Russel_Wallace

Image Credits:

- Featured Image: Alice Eastwood. Biodiversity Heritage Library, BHL Blog, Courtesy of California Academy of Sciences Archives.

- Alice Eastwood 1910, USA Public Domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Alice_eastwood.jpg

- Bergen’s botany: key and flora: Pacific coast ed. / prepared by Alice Eastwood 1901, USA Public Domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bergen%27s_botany_(Page_22)_BHL13296275.jpg

- Bergen’s botany: key and flora: Pacific coast ed. / prepared by Alice Eastwood, p. 19. USA Public Domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bergen%27s_botany_-_key_and_flora_-_Pacific_coast_ed_(Page_19)_BHL18868236.jpg

- Camp Alice Eastwood (in northeast corner), Full color Muir Woods trail map showing topographic lines for the entire region, including Muir Woods and Mount Tamalpais, 2016, USA Public Domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:NPS_muir-woods-trail-topographic-map.pdf

- A flora of the South Fork of Kings River: from Millwood to the head waters of Bubbs Creek / by Alice Eastwood., USA Public Domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:A_flora_of_the_South_Fork_of_Kings_River_(Page_6)_BHL7377732.jpg

- Foundations of botany / by Joseph Y. Bergen and Alice Eastwood. Notable Women in Natural History, p. 182. USA Public Domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Foundations_of_botany_(Page_182)_BHL23642446.jpg

- Photo by: Jim Morefield, holly gilia, Aliciella latifolia subsp. Latifolia, named after Alice Eastwood by S. Watson, J.M. Porter), Creative Commons License for educational non-commercial use. https://www.flickr.com/photos/127605180@N04/29691916547

- San Francisco Mission District burning in the aftermath of the San Francisco Earthquake of 1906, Original Photograph by: Chadwick, H. D. (U.S. Government War Department. Office of the Chief Signal Officer.) Edited by: Durova, USA Public Domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sfearthquake3b.jpg

- The Franciscan manzanita was first described as a unique species by the botanical curator of the California Academy of Sciences, Alice Eastwood in 1905. Eastwood was Peter Raven’s (Curator of the Missouri Botanical Gardens) mentor; Raven named this after her. It is now being considered for listing under the Endangered Species Act. https://www.nps.gov/goga/learn/nature/endangered-scrubland-plants.html