In 1863 taxidermist Jane Tost (c.1817-1889) was the first woman to be professionally employed by the Australian Museum, and later with her daughter Ada Rohu (1848-1928) she founded the extremely successful taxidermy and curio business – Tost and Rohu – which operated in Sydney from 1878 until the 1930’s.1

Tost and her husband Charles emigrated with their children from England to Tasmania in 1856 and worked for a time at the Hobart Town museum before relocating to Sydney in 1860.2 During the 1860’s, a dynamic new curator at the Australian Museum, Gerard Krefft, oversaw a period of intensive specimen collecting, which increased the demand for skilled taxidermy.

Krefft employed Tost in 1863 and her husband, also a taxidermist and a cabinet maker, in 1864 when another position became vacant. They were both paid at the same rate of 10 pounds per month, likely reflecting the value of Tost’s considerable expertise acquired at the British Museum in the 1840’s preparing specimens for John Gould.

An Impressive Family Tradition

Tost belonged to a prominent English family of taxidermists – she and her brothers were trained by their parents Herbert and Catherine Ward, who had bred and stuffed birds for gentleman collectors in the early 1800’s. Brothers Edwin and Frederick worked for Gould and Audubon and Tost’s nephew Rowland Ward later became internationally renowned for his big game taxidermy dioramas and “Wardian” animal furniture.3

Tost and her husband worked together at the Australian Museum until 1869, when the curator accused him, then employed as a carpenter, of misappropriating building materials for his personal use. No criminal charges were laid but he was dismissed and according to family tradition he left Sydney and his family at that time. Tost also ceased full-time employment after the incident, and although the museum refused her requests to be reinstated in the years that followed, it continued to purchase specimens from her during the 1870’s.

Tragedy and Recovery

In 1872 tragedy struck when both Tost’s son Charles and her son-in-law James Coates died from fighting a fire at the Prince of Wales Theatre near their home in the centre of Sydney. Tost and her widowed daughter had to take on the responsibility of providing for their families, so they founded the fancy work shop and taxidermy enterprise of Tost and Coates. When Coates married naturalist Henry Rohu in 1878, the firm of Tost and Rohu was born.

“All Kinds of Taxidermical Work Executed in First-class Style” 4

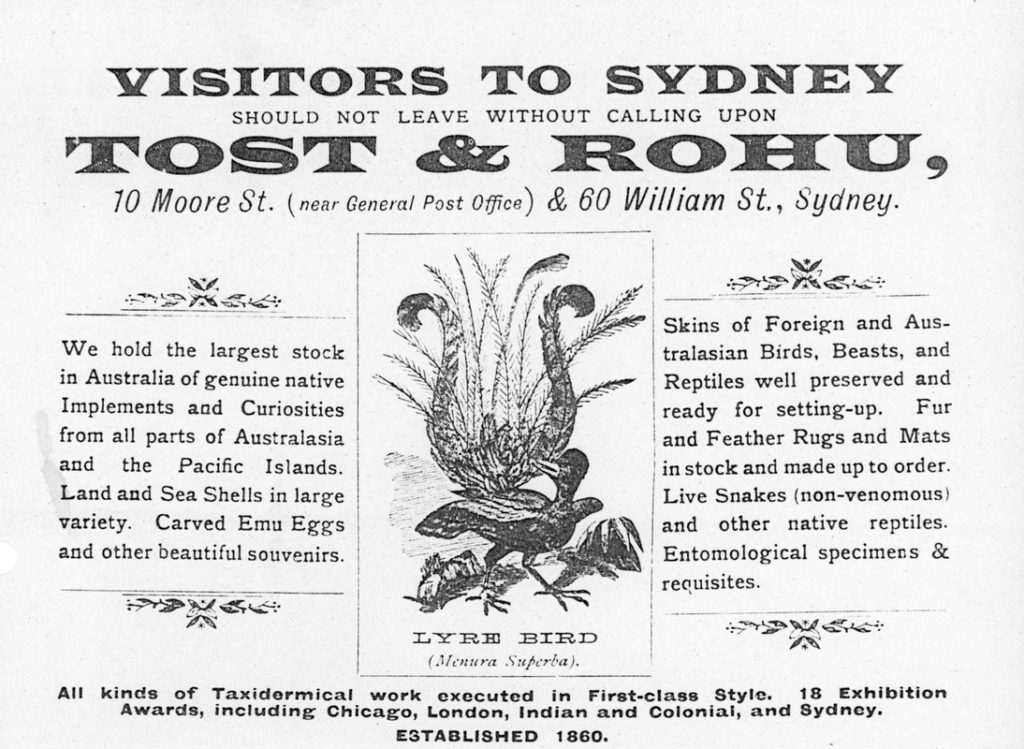

Advertising as articulators and taxidermists, fancy work and glass dome suppliers, and dealers in furs and curios, Tost and Rohu became famous for their extraordinary collections, and travelers were urged to visit their “Museum” to view the weird and wonderful collections and purchase souvenirs.

Advertising as articulators and taxidermists, fancy work and glass dome suppliers, and dealers in furs and curios, Tost and Rohu became famous for their extraordinary collections, and travelers were urged to visit their “Museum” to view the weird and wonderful collections and purchase souvenirs.

In the late nineteenth century, Sydney was a center for trade in natural history specimens and cultural items collected from the Pacific Islands and the Australian colonies, and the Australian Museum actively participated in this trade to expand its collections. The methods of collecting the cultural objects were most probably unethical by today’s standards, but the details of the interactions with the communities producing these objects were rarely documented.

The belongings sold as curios were used by Pacific Islanders and Australian Aboriginal people as weapons, tools, body adornment, and religious items, as well as for other uses5. Research examining the Tost & Rohu catalogues suggests that some of these objects were likely produced in large enough numbers to meet an external curio market demand5. However, curio collections also included items that were culturally sensitive such as secret/sacred or restricted objects, which Aboriginal people would likely not have wanted to be displayed or sold6.

Award-Winning Creations

For thirty years Tost and her daughter Rohu were the most successful New South Wales exhibitors at international shows, winning over 20 medals. They promoted their business by exhibiting examples of their work (often of Australian native animals), in London (1862 and 1886), Paris (1867), Sydney’s Garden Palace (1879), Calcutta (1883), Melbourne (1888), Launceston (1891-2), and the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago (1893). The Women’s Work committee for the Chicago exposition made a special effort to include examples by female taxidermists in their display, and Ada Rohu was the most successful Australian exhibitor, receiving ten medals.7

Although Tost died in 1889 and Rohu’s husband left her in 1895, the family business continued until the 1930’s, and during that period sold many items to the Australian Museum.

Authored by: Sue Myatt

References

- Docker, Rose,2012. The queerest shop in Australia. Explore 34(2)Winter 2012, p2-4.

- Advertisement, 1860. “Mrs Charles Tost, Naturalist..” Sydney Morning Herald (newspaper) Saturday 27 October 1860, p12

- Sear, Martha, 1999. “Curious and Peculiar? Women Taxidermists in Colonial Australia”, in J.Kerr and J.Holder(eds.) Past Present Sydney.

- Advertisement, 1908. “Snakes Furs and Curios. Tost and Rohu..” The Australian Star (Sydney newspaper) Thursday 20 February 1908, p6.

- Harrison R. Consuming colonialism: Curio dealers’ catalogues, souvenir objects and indigenous agency in Oceania. In Unpacking the Collection 2011 (pp. 55-82). Springer, New York, NY.

- Bolton L. The object in view: Aborigines, Melanesians, and museums. In Museums and source communities 2005 Jun 28 (pp. 53-65). Routledge.

- Sear, Martha, 2005. Tost, Jane Catherine (1817-1889). Australian Dictionary of Biography. Supplementary Volume, Melbourne University Press.

Illustrations

Mounted Irrawaddy squirrels. Australian Museum A3680, A3681 purchased from Jane Tost and Ada Coates in 1878. Reproduction Rights Australian Museum

Tost and Rohu’s newspaper advert from the early 1900’s.

Other Resources:

Taxidermist Extraordinaire – Jane Tost – Our First Female Employee