John Tyley, watercolor on paper of [Fruit], ca. 1802

John Tyley worked as a botanical illustrator at the historic St. Vincent Botanical Garden in the late 1700s creating exquisite depictions of tropical plants.¹ Aside from the beautiful and detailed illustrations he left behind, little is known of this native Caribbean man’s life. Here we piece together what is known of Tyley and his remarkable work.

Breaking Boundaries

He created detailed watercolors of the tropical plants of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines for Anderson’s text on the flora of St. Vincent, Hortus Sti. Vincentii Tabulae, as well as for the exhaustive plant lists Anderson kept of the garden’s plants.3 Some of these drawings including crop species such as avocado (Persea americana), cashew (Anacardium occidentale), as well as exotics like East India gooseberry (Phyllanthus acidus), Barbados Cherry (Malpighia glabra), the Malay apple (Syzygium malaccense), achiote (Bixa orellenea) and tar pot (Clusia flava).4 A collection of Tyley’s watercolor drawings and Anderson’s unpublished manuscript Hortus Sti. Vincentii Tabulae can be found in the archives of the Linnean Society.5

To fully understand how momentous an accomplishment this was for a native Caribbean man at the time, it is important to take a look at the history of St. Vincent.

Garden of Eden or Hell?

The St. Vincent Botanical Garden was established in 1765 by the British War Office and was instrumental in the colonization of St. Vincent by Britain and the subsequent establishment of slave plantations for cash crops such as sugarcane.6

Slavery was not abolished in St. Vincent until 1834, after which the land remained largely owned by wealthy plantation owners that employed Vincentians at meager wages.7 The local population largely consisted of the ancestors of escaped African slaves that intermixed with the native Carib population. They became known as the Black Caribs.7

In testament to the resourcefulness and determination of the Black Caribs, St. Vincent was one of the last of the Caribbean Islands to be colonized. In fact, in 1773, a historic treaty was signed between the Black Carib leader, Chief Joseph Chatoyer and the British – the first time the British ever signed an accord with non-white people in the Caribbean.7

In 1793 in the midst of the rebellion against colonial rule, Captain William Bligh, of the infamous Mutiny on the Bounty, delivered hundreds of breadfruit trees from Tahiti to the botanic garden. Initially meant to be a cheap source of food to feed the slaves, the breadfruit was rejected by the Black Caribs and mostly went to livestock.2

The rebellion was eventually defeated in 1796 and, in an act of utter horror, over 5,000 Black Caribs were deported to Roatán, an island off the coast of Honduras. Another 5,000 Black Caribs were exiled to a tiny island of Baliceaux off the coast of Bequia in the Grenadines, where there was little food or fresh water. Over half died in this internment camp from a deadly disease—likely yellow fever. The survivors were eventually deported to Central America where their descendants still live today.7

Well beyond the establishment of the botanical garden and during the time Tyley was likely employed there, the Carib people continued to revolt against British rule. Anderson, in his writings, expressed his racism toward the Black Carib people2, making it all the more remarkable he went on to employ John Tyley. That Tyley was able to work with this backdrop, speaks volumes of his ability and resilience in the face adversity.

Beyond John Tyley

What is known is that after slavery was abolished in 1838, many landowners abandoned their estates because they were no longer profitable.7 They left the once fertile country a disjointed landscape of resource poor monocultures of sugar, cotton and tobacco. Even so, the island passed through various states of colonization until independence was finally granted over a century later in 1979.7 At that time the Botanical Garden fell under the jurisdiction of the St. Vincent Ministry of Agriculture, where it remains today.6

Over time, as the wounds of colonization healed, the botanical knowledge and history of the landscape has returned to the hands of the people. Today, breadfruit is celebrated as an important part of St. Vincentian culture and has become a symbol of livelihood for Vincentians. The Botanical Garden remains an important cultural institution in the country and is helmed by native St. Vincentian botanist, Gordon Shallow.6 Through the work of Shallow, the Ministry of Agriculture, the Garden, the Linnean Society and the Hunt Institute, the legacy of John Tyley lives on.

Authored by: Lauren Audi

Additional Resources

Catalogue of the Botanical Art Collection at the Hunt Institute – John Tyley Watercolors: http://fmhibd.library.cmu.edu/HIBD-DB/ArtCat/recordlist.php

References

- Howard RA. The St. Vincent Botanic Garden—The Early Years. Arnoldia. 1997 Dec 1;57(4):12-21.

- Anderson A. Alexander Anderson’s Geography and History of St. Vincent, West Indies. Edited and transcribed by RA and ES Howard. London: Linnean Society of London.[Based on an unpublished manuscript in the library of the Linnean Society of London, written around 1800]. 1983.

- Bynum H, Bynum WF. Botanical Sketchbooks: With 275 Illustrations. Princeton Architectural Press; 2017.

- Fmhibd.library.cmu.edu. (2019). Catalogue of the Botanical Art Collection at the Hunt Institute. [online] Available at:http://fmhibd.library.cmu.edu/HIBD-DB/ArtCat/recordlist.php?-skip=25&-max=25 [Accessed 12 Mar. 2019].

- Anderson A. Hortus Sti. Vincentii Tabulae. Linnean Society of London.[Based on an unpublished manuscript in the library of the Linnean Society of London, written around 1800].

- Bgci.org. (2019). Botanic Garden Conservation international. [online] Available at: http://www.bgci.org/garden.php?id=314 [Accessed 12 Mar. 2019].

- Taylor C. The Black Carib wars: freedom, survival and the making of the Garifuna. St. Martin’s Press; 2012.

Image Credits

- Feature Image: John Tyley, watercolor on paper of [Fruit], ca. 1802, 27 x 42 cm, HI Art accession no. 0849.01. Image courtesy Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, Pa.

- John Tyley, watercolor on paper of Cashew [Anacardium occidentale Linnaeus, Anacardaciae], ca. 1802, 42 x 27 cm, HI Art accession no. 0849.10. Image courtesy Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, Pa.

- John Tyley, watercolor on paper of Clusia flava [Clusia Linnaeus, Clusiaceae alt. Guttiferae], ca. 1802, 42 x 27 cm, HI Art accession no. 0849.09. Image courtesy Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, Pa.

- John Tyley, watercolor on paper of East India pomerose [Myrtaceae], 42 x 27 cm, HI Art accession no. 0849.17. Image courtesy Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, Pa.

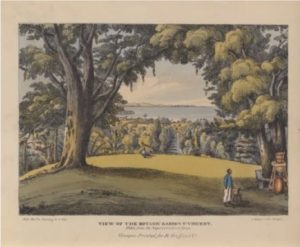

- View of the botanic garden in St Vincent, from: Lansdown Guilding. An account of the botanic garden in the island of St Vincent, from its first establishment to the present time. Glasgow: Richard Griffin & Company, 1825, King’s College London, Foyle Special Collections Library [FCO Historical Collection QK73. S2 GUI].

- Engraving of Chatoyer the Chief of the Black Caribs by Agostino Brunias and Charles Grignion. 1796. Engraving. John Carter Brown Library.