In the 1920’s a group of women artists, working mostly on commission and in insecure, part-time positions, helped create a new visual identity for the Australian Museum. They used their training in applied art and design to produce innovative and colorful natural history dioramas, and their illustrations of museum specimens were published in scientific and popular publications.

One of these women, Ethel King (1879-1939), is particularly known for her snake illustrations prepared for museum scientist J.R. Kinghorn, and for the iconic 1926 photograph of her, palette in hand, face-to-face with a mounted Giant Grouper (Epinephelus lanceolatus, also known as Queensland Groper).

Although she was a versatile and prolific artist, scientific illustrator and lithographer, like many female artists of her time, the details of King’s professional life were not well documented. We can only piece together her story by viewing the evidence of her wonderful art and a few details from the museum records and newspaper reports of the time.

The Growth of an Artist

King grew up in the small town of Lismore in New South Wales Australia, regularly entering her drawings of animals and flowers into the local shows and winning prizes and recognition for her work. She moved to Sydney to study with the notable artist Julian Ashton at his Sydney Art School, and at North Sydney Technical College from 1909-1913 she completed courses in the applied arts, gaining honors in modeling and plaster casting. A fellow student who also excelled at modeling was Phyllis Flockton Clarke, who King would later work with at the Australian Museum.

Many years later King recounted for The Australian Woman’s Mirror how she came to be hired by the Australian Museum in 19241. She had set herself the personal challenge to perfect the casting and painting of fish by studying and experimenting on fish purchased from local markets. Eventually her models were displayed in a window at Sydney’s Martin Place, where they captured the interest of the museum curators who ultimately hired King for her extraordinary talent, albeit on a temporary basis only.

The Story Behind the Grouper Photograph

In May 1925, King and the Australian Museum received a major commission for the preparation of a Queensland grouper and other fish for the Fijian government to display in the New Zealand and South Seas International Exhibition in Dunedin2. This project proved to be a challenge for the lead taxidermist Henry Grant and his assistants as the specimens were larger than originally considered; as part of the process they had to custom-build a tank large enough to fit the 250-pound grouper! The fishes arrived by ship from Fiji frozen in huge blocks of ice, and as they thawed King completed all the sketches and drawings. The specimens were then measured and skinned, and the skins placed in alcohol for preservation.

Given the size of the grouper, a wire gauze and paper pulp manikin was constructed, and the preserved skin carefully placed over it. By now it was December 1925, and King had to go to hospital for an operation. The specific illness was not revealed but her condition was worse than anticipated and she returned home to Lismore to convalesce with her family. In mid-January the museum sent a telegram to King asking if she could commence the coloring “at once”, but she was still unwell. A well-known Sydney artist Mr.Thomas attempted the work, but it appeared only King had the skills to complete the painting. Another telegram was dispatched, and despite being “in a delicate state of health” King returned to Sydney and completed her work by 1 March 1926, when the grouper was finally sent to the exhibition where it was admired by thousands of attendees.

A Woman of Many Accomplishments

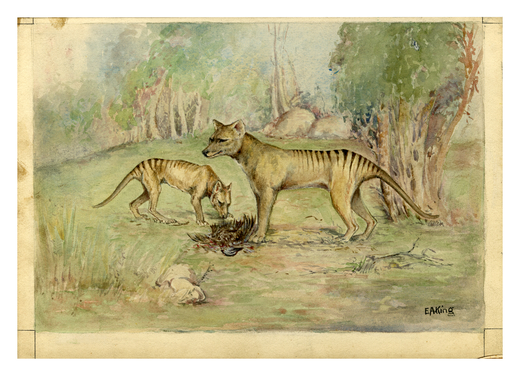

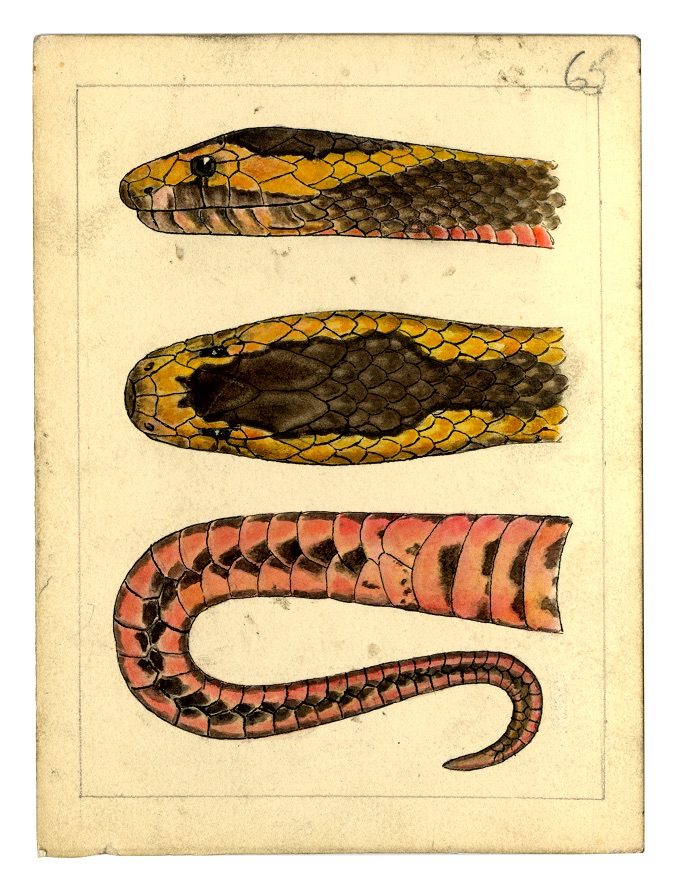

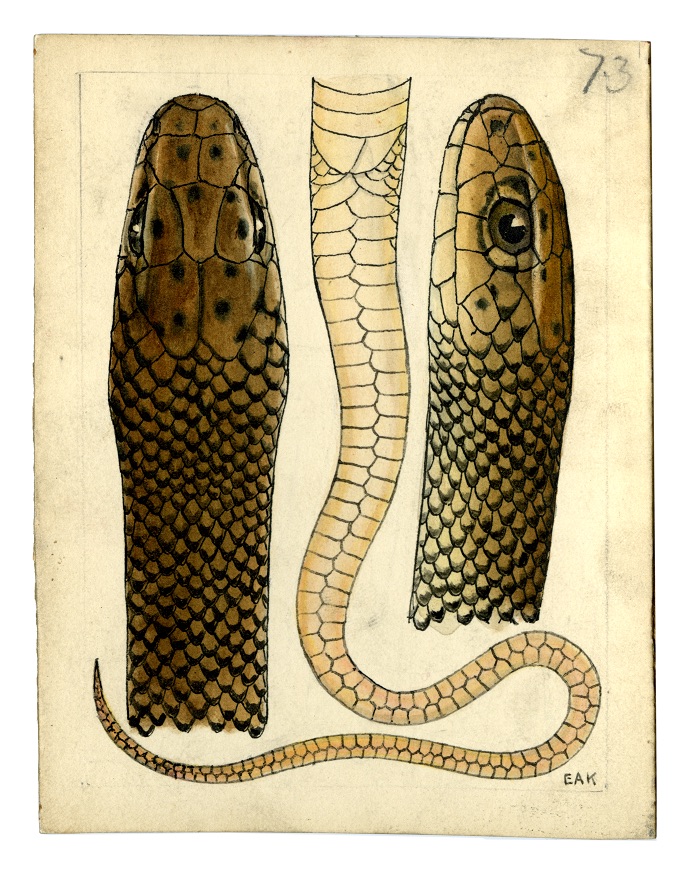

In addition to various artistic commissions for museum specimens and dioramas King created 137 watercolors of snakes for J.R. Kinghorn’s publication “Snakes of Australia” 3, and a series of Australian fauna watercolor illustrations which the Australian Museum produced as postcards in 1929.

Before her time at the Australian Museum, King spent four years at the Sydney Botanic Gardens drawing lithographs for J.H. Maiden’s monumental work, “The Forest Flora of NSW” (1920-1924)4, and she also provided scientific illustrations for the Australian Encyclopedia. In the 1930’s she illustrated W.W. Froggatt’s “Australian Spiders and their Allies” 5, and “Water Life” 6, a popular nature book by Charles Barrett which included contributions from Australian Museum scientists.

King also worked on contract for the Australian Institute of Anatomy in Canberra, where she was about to take up the position of anatomical artist for the Science Congress in 1939 when she died suddenly at only 58 years old. On her death the Australian Museum Director Charles Anderson (1939) praised her as “a most faithful delineator”- a legacy which continues to live on today in the museum’s galleries and archives7.

Authored by: Sue Myatt

References

- Anonymous, 1935. Making dead things live again, The Australian Woman’s Mirror, Vol.11 No.22 p17

- Whitley, G.P., 1926. A giant fish. The Australian Museum Magazine Vol.2 No.10 p353. Australian Museum, Sydney

- Kinghorn, J. R., 1929. Snakes of Australia, with 137 drawings by Ethel A. King. Angus & Robertson, Sydney

- Maiden, J. H., 1902-1924. The forest flora of New South Wales (8 Volumes) Forest Department of New South Wales. W A Gullick Government Printer, Sydney

- Froggatt, Walter W., 1935. Australian spiders and their allies Royal Zoological Society of New South Wales, Sydney

- Barrett, Charles, 1933. Water Life Sun News Pictorial, Melbourne Victoria

- Anderson, Charles(editor), 1939. Notes and news, Australian Museum Magazine Vol 06 No 12, p41. Australian Museum, Sydney

Photo Credits

- Featured image: Preparation of a Queensland Groper by Ethel King, 1926. Photographer George C. Clutton. Australian Museum Archives AMS351_V09193. Reproduction Rights Australian Museum

- Ethel King’s watercolour and ink drawing of the Tasmanian Tiger, Thylacinus cynocephalus, prepared for an Australian Museum postcard series, 1929. Australian Museum Archives AMS118_6. Reproduction Rights Australian Museum

- Watercolour by Ethel King of the Golden Crowned snake Cucophis squamulosus, 1929. Australian Museum Archives AMS601_64. Reproduction Rights Australian Museum

- Watercolour by Ethel King of the Spotted-Headed snake Desmansia olivacea, 1929. Australian Museum Archives AMS601_72. Reproduction Rights Australian Museum