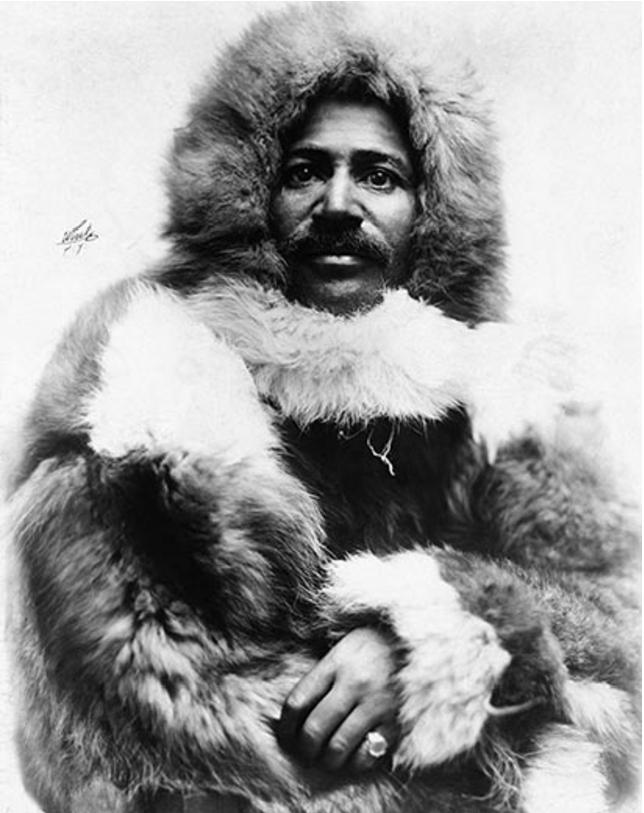

Matthew Henson

A member of the first expedition to reach the North Pole, Matthew Alexander Henson was an experienced member of several polar missions and essential to the success of Robert Peary’s famous explorations.1

Featured Image: Matthew Henson in Greenland in 1901.

Henson was born on a farm on August 8, 1866 in Maryland at the end of the Civil War.5,6 His parents were born free, unlike most other black people who lived in the United States at that time as slavery was not abolished until ratification of the 13th Amendment in 1865.1, 2, 3, 4

Henson lost both of his parents at a young age; his mother died when he was only two years old, and his father when he was eight.7 Henson escaped an unhappy childhood and ran away to live with an uncle he had never met in Washington, DC.6

An Unexpected Mentor

At age 12, Henson took up a job in a restaurant as a dishwasher.5 This is where his inspiration to seek adventure as a sailor and his urge to see the world emerged. He overheard customers talk about the docks of Baltimore and the large ships that embarked from these docks to sail the world. At age 13, Henson quit his job and hiked to Baltimore, signing on as a cabin boy on a ship, the Katie Hines, bound for Hong Kong.5The ship would be Henson’s home for the next five years.

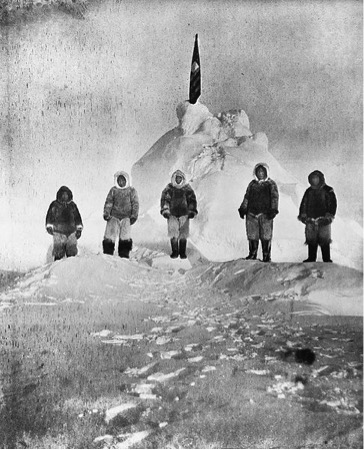

Matthew Henson (center) and four Inuit guides, Ooqueah, Ootah, Egingwah, and Seegloo (from left to right). Photo by: Robert Peary

The ship’s captain, Captain Childs, a Quaker, became Henson’s first and only real teacher. He taught Henson reading, writing, seamanship, and navigation, including how to hoist sails, tie knots, and read charts, as well as lessons in geography, history, mathematics, and first aid.1,6

In 1883, Captain Childs died on a voyage at sea. Henson owed a lot to Captain Childs, and remembered the captain’s dying words: “Life is a journey to death, Matthew. Live as well as you can, learn from all that comes, for Death is an even greater and more exciting adventure.” 8

Eskimos with dogs and sledges, Peary Auxiliary Expedition, Inglefield Gulf, 1894.

A Coincidental Meeting

Henson returned to DC at age 19 and took a job as a stock boy in a men’s clothing store. Robert E. Peary, a US Navy civil engineer, went to that same store in 1887 to buy a tropical sun helmet after being recently re-assigned to Nicaragua.

Henson was called to bring out the sun helmet. Peary introduced himself to Henson after hearing about his excellent work from the store owner, and invited him to join his expedition to Nicaragua. Henson accepted this travel opportunity, in which he served as a field assistant to the surveying crew.6

So began a relationship in which Henson and Peary traveled and learned together for more than 20 years, including their Arctic expeditions in 1891, 1893, 1896, 1897, 1898, 1905, and 1908.1,5,6

Marriages, and The Birth of a Son

After working at the clothing store in Washington, DC and returning from Nicaragua with Peary, Henson moved to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in 1889. He initially felt like an outsider in the new city, but soon made friends.

There, he met Eva Helen Flint and they soon talked of marriage, which happened on April 16, 1891. That same year, Henson joined Peary on their first Greenland expedition, and in 1893 for a second expedition. The frequent expeditions in quick succession after marriage caused friction with Henson’s new wife Eva Flint and her family.

Henson and Flint divorced in 1897, after Henson again joined Peary on an expedition to Greenland.1 In September 1907, Henson married his second wife, Lucy Jane Ross, remaining married to her throughout life. Henson did not have children with either of his wives.

Matthew Henson in Arctic costume on deck of the “Roosevelt” on arrival at Sidney, Nova Scotia

The Roosevelt (Robert E. Peary’s ship) at Cape Sheridan

The late S. Allen Counter, a distinguished African-American Harvard University professor, became interested in Henson during the 1980s.1,9 He heard rumors that Henson had a grown son named Anauakaq, his only heir, living in the Arctic, born to an Inuit woman named Akatingwah.

Counter traveled up north to meet the son and brought Henson’s Inuit relatives to the United States to meet the rest of Henson’s family.1 Counter also sought and gained proper recognition from the United States for Henson’s contributions to Arctic exploration through persistent advocacy of his remains to be interned at Arlington National Cemetery.9,10

A Most Capable Arctic Explorer

Peary received criticism for hiring Henson, a black man, as his assistant, a practice which was not common at the time. People questioned why he did not take one of his white assistants.5 As a black man, Henson worked for a smaller salary than any other party of the expeditions.11

However, Henson was the only man who had mastered the skills required to reach the North Pole: prior experience with polar exploration, orienteering, traveling over rough polar sea ice, repairing ships, building and repairing sledges/sleds, building shelter/igloos, speaking the Inuit language, hunting for food, making warm clothing from furs, building igloos, carrying food and fuel, training and driving the dog sleds across snow and ice, tending to the dogs and keeping them healthy, and dressing to withstand below-freezing Arctic temperatures.

Captain Robert Peary’s North Pole Expedition, 1905-06. “On the sled that went to the North Pole”. Pictured are Donald Baxter MacMillan, George Borup, Thomas Gushue (1st Mate of the Roosevelt, and Matthew Alexander Henson, between 1906-09).

Drawings of polar bear, musk ox, reindeer, foxes, Greenland.

In the words of commander Donald B. McMillan, also on the journey to the North Pole, “[Henson]…made every sledge and cook stove used on the route to the pole. Henson was altogether the most efficient man with Peary.”11

Henson is credited with saving Peary’s life at least twice, once when Peary nearly drowned and another time when a musk ox attacked him. Henson also cared for Peary when Peary got frostbite and gangrene in the Arctic. Henson learned a lot from the Inuit people of northwest Greenland, the communities of Moriussaq and Qaanaaq of the Smith Sound area, and was the crew member most fluent in the Inuit language, Greenlandic Inuktitut, likely “Polar Eskimo” language (North Greenlandic/Avanersuarmiutut, a Thule Inuit dialect or Kalaallisut).6,12

He was also skilled in befriending the Inuit people; whereas the Inuit people liked Peary for his gifts in exchange for their help, they saw Henson as a friend. They nicknamed him Maripaluk, or “kind Matthew.” 1,6

In his autobiography of 1912, Henson gave credit to the Inuit peoples’ valuable help in the polar expeditions, stating “It is true that the Esquimos are of little value to the commercial world, due probably to their isolated position; but these same…people have rendered valuable assistance in the discovery of the North Pole.” 2

Henson also accompanied Peary on his mission to recover and transport three meteorites from the Arctic, currently on display at the American Museum of Natural History in the Arthur Ross Hall of Meteorites. The museum purchased these from Peary for $40,000. The meteorites were recovered from Greenland during the expeditions that Peary and Henson made in 1896 and 1897.5,6

Matthew A. Henson immediately after the sledge journey to the Pole and back

Child viewing the Cape York meteorite, Ahnighito, Memorial Hall, February, 1920

The Inuit peoples referred to meteorites as “stones from heaven”; for many Indigenous people, meteorites are considered powerful and they attach a spiritual significance to them. For centuries, the Inuit people of Northern Greenland also used the “Great Iron” from the meteorites as a resource to make hunting tools and weapons, like knives, arrowheads, lances, and harpoon blades and tips. They were protective of the meteorites from “iron mountain.”

In 1894, the Cape York meteorites were found by convincing a local Inuit hunter, Aleqatsiaq, to share the location.16 It was told by hunter Aleqatsiaq that, “We have a legend, old, old…It is that during a long night the blocks came from heaven, lighting the darkness brighter than the sun, roaring, hissing, crashing like the rending of an iceberg, and shaking the earth as if the sun himself had burst.

The Woman [the second largest of the three meteorites, originally looking like a female sitting and sewing], who owned the Dog [the smallest of the three] and lived in the Tent [also known as “Ahnighito,” the largest of the three], was found. Tornasuk, the Evil Spirit, threw all three from the skies.” 17

Six people made it to the North Pole on April 7, 1909: Henson, with his two Inuit aides Uutaaq and Ukkujaaq, and Commander Peary, with his two Inuit aides, Iggiannguaq and Sigluk.1,2,3,4 Looking back at that day, even at age 80, Henson was pleased overall.8 In an article about the North Pole expedition, he described April 6, 1909 as “the happiest day of my life.”11

There are two differing accounts of their reaching the North Pole, with either Peary and Henson arriving together and another in which Henson reached the North Pole first with an Inuit aide and Peary arrived later by sled due to his physical weakness and older age.

The four Inuits, Egingwah, Ooqueah, Ootah, and Seegloo, who accompanied Matthew Henson and Robert Peary on their voyage to the pole. From Henson’s own photograph.

Henson went on to write two books about his arctic explorations, first A Negro Explorer at the North Pole, in 1912 and later in collaboration with Bradley Robinson in 1947, he co-wrote his biography, Dark Companion: The Story of Matthew Henson

Arctic exhibit, AMNH

Sharing Arctic Knowledge

Peary gained a great deal of fame for commanding the expeditions to the Arctic, writing books, and lecturing across the country. He took ownership of the polar summit story and the photographs from the expeditions. Henson was somewhat constrained in his ability to lecture, but he was ultimately permitted to give a trial lecture to the public in New York City, with recommendations from the American Museum of Natural History. Henson would speak about the habits, modes of living, and the customs of the Inuit people, with photographs he took on Arctic expeditions.11

In the late 1800s, in between Arctic expeditions, Henson was a staff member in the taxidermy department at the American Museum of Natural History. There he worked on the Arctic exhibit displays, skinning and mounting the walrus (and other animal) skins, arranging the far North exhibits of animals, and setting up the backgrounds to accurately reflect Inuit villages on hunting trips with skin tents and snow igloos.5,6

A poem found in Henson’s diary:

Remembered by What I Have Done

Up and away, like a dew of the morning

That soars from the earth to its home in the sun;

So let me steal away, gently and lovingly

Only remembered by what I have done.

My name, and my place, and my tomb all forgotten,

The brief race of time well and patiently run

So let me pass away, peacefully, silently,

Only remembered by what I have done.

Gladly away from this trail would I hasten,

Up to the crown that for me has been won.

Unthought of by man in rewards or in praises—

Only remembered by what I have done.

Not myself, but the truth, that in life I have spoken;

Not myself, but the seed that in life I have sown

Shall pass on to ages—all about me forgotten,

Save the truth I have spoken, the things I have done.

Sincerely yours

Matthew Alexander Henson

-Matthew A. Henson Collection, Morgan State University, Baltimore, Maryland10

Matthew A. Henson: A Negro Explorer at the North Pole (New York, 1912)

Matthew A. Henson: A Negro Explorer at the North Pole (New York, 1912)

Racism and Delayed Recognition

Whereas Peary gained recognition as a hero for reaching the North Pole, received many awards, published his story, and gave lectures, Henson’s achievements went unnoticed by many people for many years.1 When historians set to work on writing Peary’s life, they explained Henson’s role, but immediately dismissed him and sought to minimize his contributions.,8 This inaccurate description was at odds with the truth, that Henson was a crucial crew member throughout their expeditions. His accomplishments received greater recognition within the black community. He lectured at historically black colleges and was honored with two Master of Science degrees, one from Morgan State College and one from Howard University.1,8,13

Henson retired at age 70, after working for more than 25 years in modest jobs after his exploration days.1 Roughly thirty years after his Polar feat, Henson and Uutaaq, an Inuit man who helped on the North Pole expedition, were finally elected as members of The Explorers Club in New York City in 1937. The club only included people who had undertaken serious exploration voyages.1,9 Today, the mittens Henson wore during his 1909 expedition with Peary to the North Pole can be seen at The Explorers Club.9 During his retirement, he received recognitions from the Geographic Society of Chicago, US Congress, Dillard University, and even from President Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1954.13

In June 1945 (36 years after reaching the North Pole in 1909), Henson received the US Navy Medal, along with all the other American members of Peary’s expedition.1,11 However, because he was black, Henson was denied an invitation to attend the ceremony where the others received their medals.1 Some years later, another ceremony was held to apologize for the injustice1. He also received a Silver Loving Cup from the Bronx Chamber of Commerce.11 In 2000, the National Geographic Society recognized Henson with the Hubbard Medal for distinction in exploration, discovery, and research.13The American Geographical Society awarded a gold medal to Henson (posthumously) on the centennial of his involvement in Peary’s 1909 expedition for significant accomplishment in a polar region.14

Remembering Henson

Henson died on March 9, 1955 at age 88; he was living in the Bronx.11 After his death, the state of Maryland placed a plaque in its state house in his honor, the first black person to receive this recognition and the governor declared April 6, 1959 as Matthew Henson Day in his honor.5 In 1988, Henson and his wife, Lucy, were reburied at Arlington National Cemetery with other national heroes, near Robert Peary’s grave.1

One of the honorable pallbearers, John H. Johnson, delivered the memorial address at the reinterment of Henson’s remains at Arlington National Cemetery on April 6, 1988, the 79th anniversary of the North Pole discovery, stating:

“Matthew Henson taught us all a great deal. He taught us to be independent. He taught us to achieve. He taught us to make the most out of whatever opportunities are before us, while trying at all times to improve those opportunities. Henson was a proud man. He did not receive the recognition that he deserved, but he never complained. I remember reading about his speech to the Chicago Geographical Society in which he said he had only sought to serve—that he was not bitter—that he knew what he had done—and that he had his own particular kind of pride. And so I would say, the world is better for Henson. The world has a better feeling about achievement—about a man who was willing to pay the price—a man who once said nothing had ever been given to him. He had always earned it. Matthew Henson has earned the recognition he is receiving today.” 10

Tombstone of Matthew Henson, Arlington National Cemetery

Some of Henson’s relatives from the USA and Greenland came for the memorial ceremony.10

“Ahdoolo,” a word expressing hope, courage and perseverance that Henson had made up to rouse the Inuit early in the morning for a tough day on the trail, was also adopted by the Inuit people into their language. “It always made them laugh to wake up to its un-Eskimo sounding tones.” 5 This was a powerful expression of the love and respect that they had for Henson.5

Peter Freuchen, a Dane and another Arctic explorer who lived in Greenland among the Inuit for many years and author of Book of the Eskimos, had this to say about Henson:

When I first went to live with the Smith Sound Eskimos, it was not long before I became acquainted with the strange songs and fabulous legends relating the greatness of a man the natives called ‘Miy Paluk.’ I had followed Peary’s North Pole expedition into that country by a year and so I soon realized that the man around whom these stories had grown was Matthew Henson. It was not until many years later that I met Matt Henson for the first time in America. I was thrilled, as one would be, to shake the hand of this mortal whom I’d first come to know as a hero magnified by Eskimo legend to immortal proportions. To the Eskimos, who loved him, Matt was the greatest of all the men who came from the distant Land of the South.” 5,8

A fragmented portrait titled Matthew Henson 2012 by artist Tavares Strachan, MFA

Continuing to Honor the Legacy of Henson

Artist Tavares Strachan, a Yale MFA graduate originally from the Bahamas, considers Henson his hero and has created artwork inspired by Henson. This includes a collage-form portrait made from images of his life and another piece entitled How I Became Invisible.15

In Maryland, there are at least three schools, two elementary schools and one middle school, a neighborhood association, an avenue, as well as a State Park and trail, that are all named after Henson. There was a public housing project in Phoenix, Arizona also named after him.

While Henson garnered some recognition for his accomplishments, albeit mostly later in his life or posthumously, we include his story here on the Untold Stories website as many people are unaware of the integral role he played in Arctic exploration and reaching the North Pole.

As part of this work, the Untold Stories team worked with the American Museum of Natural History in New York City to amend the Arthur Ross Hall of Meteorites exhibit. The exhibit now features an image of Henson and recognizes his accomplishments; it also lists the names of the four Inuit guides that were crucial to the 1909 expedition.

Turkey Run Stream restoration work, Matthew Henson Trail

Authored by: Varsha Mathrani

References

- Gaines, Ann Graham. Journey to Freedom: Matthew Henson and the North Pole Expedition. The Child’s World, North Mankato, 2010.

- Henson, Matthew A. A Negro Explorer at the North Pole. Arno Press & The New York Times, New York, 1969.

- Henson, Matthew A. A Black Explorer at the North Pole. University of Nebraska Press, A Bison Book, Lincoln, 1989.

- Henson, Matthew A. Henson at the North Pole. Dover Publications, Inc., 2008. (Books 2, 3, and 4 are different editions of Henson’s own autobiography of his travels with forewords and introductions by different people, and Book 8 is a biography based on interviews with Henson; They both are Black Heritage Reference Center books.)

- Gilman, Michael. Matthew Henson: Explorer. Chelsea House Publishers, 1988.

- Hayden, Robert C. 7 African American Scientists. Twenty-First Century Books, 1992. p. 84-109.

- Beckner, Chrisanne. 100 African-Americans Who Shaped American History. Bluewood Books, 1995. p. 37.

- Robinson, Bradley with Matthew Henson. Dark Companion: The Story of Matthew Henson. Fawcett Publications, Inc., 1967.

- The Explorers Club. North Pole. Retrieved from https://explorers.org/about/history/north_pole

- Counter, S. Allen. North Pole Legacy: Black, White, and Eskimo. The University of Massachusetts Press, 1991.

- AMNH Vertical File about staff member Matthew Henson. Special Collections, AMNH Research Library.

- Cottom, Ric & Lisa Morgan. Fresh Air with Terry Gross. The Explorer (Matthew Henson), 2018. Retrieved from http://www.wypr.org/post/explorer-matthew-henson

- Weatherford, Carol Boston. I, Matthew Henson: Polar Explorer. Walker & Company, 2008.

- Kaplan, Susan A. & Robert McCracken Peck. North by Degree: New Perspectives on Arctic Exploration. American Philosophical Society, Lightning Rod Press series, Philadelphia, 2013.

- Pomeranz Collection Tavares Strachan art. Retrieved from http://pomeranz-collection.com/?q=node/214

- Wikipedia about Tavares Strachan. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tavares_Strachan

- Tavares Strachan Artsy website. Retrieved from https://www.artsy.net/artist/tavares-strachan

- Isolated Labs: Studio Tavares Strachan website. Retrieved from https://isolatedlabs.com/

- Peary, Robert E. Northward Over the Great Ice: A Narrative of Life and Work Along the Shores and Upon the Interior Ice-Cap of Northern Greenland in the Years 1886 and 1891-1897. V2. Frederick A. Stokes Company, 1898. Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books?id=vNSfAAAAMAAJ

- Porter, Raymond. A Seventy-five-thousand-pound Meteorite. Pearson’s Magazine, Volume 13. Pearson Publishing Company, 1905. Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books?id=IbMRAAAAYAAJ

Additional Resources

- Gaines, Ann Graham. Matthew Henson and the North Pole Expedition. Retrieved from https://childsworld.com/shop/show/2396

- OBP. North Pole Promise, 2014. Retrieved from https://www.opb.org/pressroom/pressrelease/north-pole-promise-/

- Gibbons, Russell. Matthew Henson: Black Explorer Used and Discarded by Peary. NYTimes, 1987. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/1987/06/21/opinion/l-matthew-henson-black-explorer-used-and-discarded-by-peary-8488.html

- NPR Morning Edition about Hark! A Vagrant by Kate Beaton, 2011. Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/2011/09/29/140804195/hark-from-dna-to-jfk-a-comic-take-on-history

- Henson and Peary, PBS Learning Media, NY. Retrieved from https://ny.pbslearningmedia.org/resource/pbs-world-explorers-henson-peary/pbs-world-explorers-henson-peary/

Image Credits

- Featured Image: Matthew Henson in Greenland in 1901. Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Matthew-Henson-8.jpg

- Matthew Henson (center) and four Inuit guides (Ooqueah, Ootah, Egingwah, and Seegloo). Photo by: Robert Peary, Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Matthew_Henson_and_four_Inuit_guides.jpg

- Eskimos with dogs and sledges, Peary Auxiliary Expedition, Inglefield Gulf, 1894. Research Library | Digital Special Collections, accessed November 1, 2018, http://lbry-web-007.amnh.org/digital/items/show/301.

- Matthew Henson in Arctic costume on deck of the “Roosevelt” on arrival at Sidney, Nova Scotia. PICRYL, https://picryl.com/media/matt-henson-of-pearys-crew-in-arctic-costume-on-deck-of-the-roosevelt-on-arrival-1

- The Roosevelt (Robert E. Peary’s ship) at Cape Sheridan. Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Roosevelt_Cape_Sheridan.jpg

- Captain Robert Peary’s North Pole Expedition, 1905-06. “On the sled that went to the North Pole”. Pictured are Donald Baxter MacMillan, George Borup, Thomas Gushue (1st Mate of the Roosevelt, and Matthew Alexander Henson, between 1906-09. George Bain Collection. (2015/10/16).Lot 11059-4 (LC-DIG-GGBAIN-68223). This image was originally posted to Flickr by Photograph Curator at https://flickr.com/photos/127906254@N06/21635170314. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Men_and_sled_that_went_on_Peary%27s_North_Pole_Expedition,_1905-1906_(LC-DIG-GGBAIN-68223)_(21635170314).jpg

- Drawings, polar bear, musk ox, reindeer, foxes, Eskimo, Greenland. American Museum of Natural History Special Collections, accessed November 1, 2018, http://lbry-web-007.amnh.org/digital/items/show/44813.

- Tellikotinah, the Smith-Sound Inuit hunter-guide, who led Peary and Henson to the ‘Saviksue’ or great Cape-York meteorites. The Smith-Sound Inuit are the most northerly human beings in the world. https://www.flickr.com/photos/internetarchivebookimages/20438204270/ (https://books.google.com/books?id=vNSfAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA330&lpg=PA330&dq=Tellikotinah&source=bl&ots=wt7TuQl6EM&sig=ACfU3U0Em3W8_m6M0Q5H4Qt_CZfUjQrG5A&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjcwMX04obgAhUj1lkKHRtkC1AQ6AEwAHoECAEQAQ#v=onepage&q=Tellikotinah&f=false https://malagabay.files.wordpress.com/2014/04/greenland-the-cape-york-iron-meteorites.jpg

- Matthew A. Henson immediately after the sledge journey to the Pole and back. Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Matthew_Henson_return.jpg

- Child viewing the Cape York meteorite, Ahnighito, Memorial Hall, February, 1920. American Museum of Natural History Research Library | Digital Special Collections, accessed November 1, 2018, http://lbry-web-007.amnh.org/digital/items/show/47856

- The four Eskimos, Egingwah, Ooqueah, Ootah, and Seegloo, that accompanied Matthew Henson and Robert Peary on their voyage to the pole. Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:North_Pole_eskimos.jpg

- Matthew Henson, ~1912. From Matthew A. Henson: A Negro Explorer at the North Pole (New York, 1912). Retrieved from http://www.gutenberg.org/files/20923/20923-h/20923-h.htm. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Matthew_henson.jpg

- Arctic exhibit, AMNH “Peary Arctic Club exhibit, 1909,” American Museum of Natural History Research Library | Digital Special Collections, accessed November 1, 2018, http://lbry-web-007.amnh.org/digital/items/show/56124

- Matthew Henson holding an image of Robert Peary, 1953. New York World-Telegram and the Sun staff photographer: Roger Higgins – Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cph.3g07506. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?search=%22matthew+alexander+henson%22&title=Special:Search&go=Go#/media/File:Matthew_Henson_NYWTS.jpg

- Tombstone of Matthew Henson, Arlington National Cemetery. Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Matthew_Alexander_Henson_(24819590555).jpg

- Matthew, 2011-12. Collage, pigment, paper, mounted on sintra, encased in Acrylic, Four panels; 30 x 40 inches ea., 80 x 60 inches overall, Courtesy of the Artist, Tavares Strachan.

- Turkey Run Stream restoration work, Matthew Henson Trail. This image was originally posted to Flickr by TrailVoice at https://flickr.com/photos/44066905@N00/3508388376. It was reviewed on 28 November 2015 by FlickreviewR and was confirmed to be licensed under the terms of the cc-by-sa-2.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Matthew_Henson_Trail-6.jp