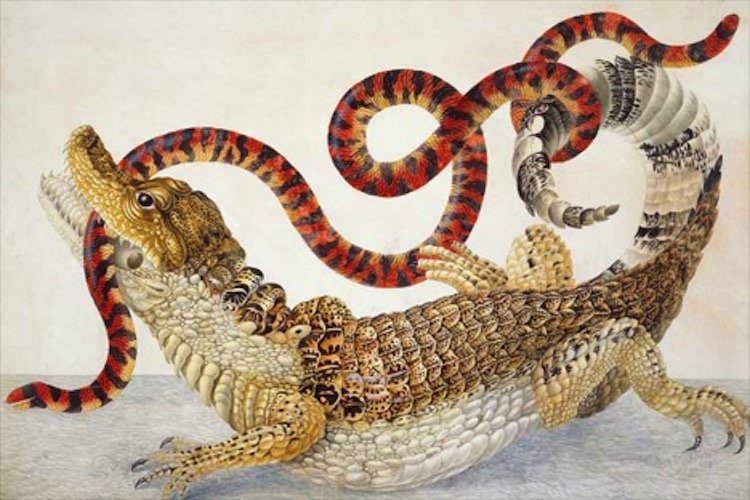

Illustration of a Spectacled Caiman (Caiman crocodilus) and a False Coral Snake (Anilius scytale) (1701–1705) by Maria Sibylla Merian, watercolor and gloss over etching on parchment

“Ever since my youth I have been engaged in the examination of insects. …I set aside my social life and devoted all my time to these observations and to improving my abilities in the art of painting, so that I could both draw individual specimens and paint them in lively colors.”1 -Maria Sibylla Merian

Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717) was a native German copperplate engraver, watercolor and botanical artist, entomologist-naturalist, adventurer, and publisher. She devoted her talents to the mysteries of insect development and created beautiful artworks of her subject matter. She published accounts demonstrating the continuity in life stages of holometabolous insects (i.e. insects that undergo complete metamorphosis), as opposed to each stage being considered completely distinct species, as many believed at the time. Holometabolous insects account for 85% of insect diversity, with consecutive life stages of egg, larva, pupa, and finally, adult.2

Her Early Years

Maria Sibylla Merian was born on April 2, 1647 (a year before the end of the Thirty Years’ War) in Frankfurt, Germany.1 She lived during what is now considered the Golden Age of still life and flower paintings.3

Merian was born into a guild family of engravers and publishers.1,2 Her extended family were religious refugees, Calvinists fleeing the Catholic Church, moving from one place or another.4

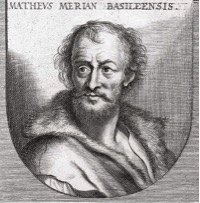

Her father, Matthaus Merian the Elder (1593-1650), owned a printing press and engraved and published his own books. He was best known for a series of illustrated journeys to the New World.3,4 He died when Merian was only three years old. Her mother, Johanna Sibylla Heim, remarried a still-life painter named Jacob Marrel (1613-1681).

As a girl, Merian was forbidden from officially participating in an apprenticeship, so her stepfather, her brothers, and their apprentices, all skilled artists, taught her at home instead. The young Merian loved it.1,4,5

A New Persepective

Unlike other painters at the time, who focused on floral still-life and learned their craft in the studio by copying other artists’ paintings of isolated flowers, Merian was interested in flowers in their natural habitat, with insects.1 She was drawn to the beauty of insects as a young girl, sketching and painting images of caterpillars on their host plants, and observing their transformation into moths and butterflies.2

By age thirteen, Merian was collecting and observing silkworms and watching caterpillars crawl along the ground outside.1,8 Merian started bringing the insects into her home and kept a small colony of silkworms, feeding them mulberry leaves and lettuce scraps.6 She took notes and painted them as they ate, spun themselves into a “date pit” (a German expression for cocoon), and burst open.6 Her mother, Johanna, worried about her interest in insects, believing Merian’s obsession started when Johanna looked at a collection of bugs while pregnant with Merian.4

At the time, naturalists were not paying a great deal of attention to insects. Many people believed insects came out of the ground (“spontaneous generation”), not understanding their life cycle or how they reproduced.4

“[I collected] all the caterpillars that I could find, in order to observe their metamorphosis. I therefore withdrew from society and devoted myself to these investigations; at the same time I wished to become proficient in the skill of painting in order to paint and describe them from life.” 7-Maria Sibylla Merian

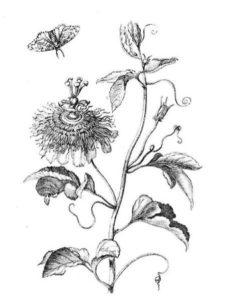

Merian discovered that many butterflies concentrate on one particular host plant for food. They lay their eggs on this particular plant species and the caterpillars eat the leaves, growing bigger before developing into a chrysalis and finally emerging as a butterfly. Because of this host-plant specificity, Merian always painted the host plant, which was the source of food, together with the creature in all its stages of development.3

“When put on a warm hand it started moving vividly and you could clearly see that inside the changing caterpillar, or better inside its date kernel [her name for pupa] was life nevertheless. But if cut open too early…nothing but colored watery material comes flowing out.” 7 -Maria Sibylla Merian

Marriage and Beyond

When she was eighteen, Merian married one of her stepfather’s students, Johann Andreas Graff (1636-1701)2,9; they were married for twenty years, although it was not a smooth marriage. Johann and Merian had two daughters, Johanna Helena (born in 1668) and Dorothea Maria (born in 1678), to whom Merian taught painting.4,5,9

In 1670, at the age of 23, Merian set up a school for painting and embroidery in Nuremberg.5,9

New Book of Flowers

Between 1675 and 1680, she published Neues Blumenbuch (New Book of Flowers), a collection of floral engravings, in three installations. These were used as pattern books for painting and embroidery.2,5,9 This book was remarkable for its brilliant colors, artistic quality and botanical accuracy.

In 1677 and 1680, she published two further sets illustrating the metamorphosis of insects, including butterflies. One set included a painting of caterpillars being attacked by parasitic wasps.2

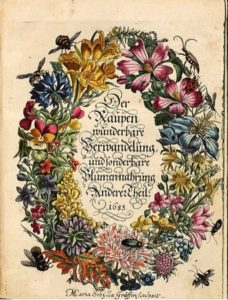

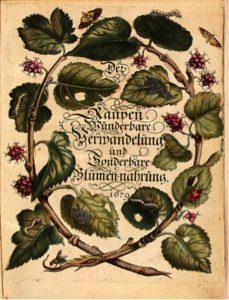

The Wonderful Transformations of Caterpillars

In 1679 and 1683, respectively, Merian published her two-volume Der Raupen wunderbare Verwandlung (The Wonderful Transformation of Caterpillars).5

In 1681, she abandoned her school for painting and embroidery and returned to Frankfurt.5

In 1685, she left her husband due to an unhappy marriage and joined a Protestant commune in Wieuwerd, Holland. She lived in this Dutch village at a residence owned by the first governor of Dutch Suriname, named Cornelis van Aerssen van Sommelsdijck (1637-1688).2,19 This is when Merian first became intrigued by the tropics.

“I saw with wonderment the beautiful creatures brought back from the East and West Indies…” 7 -Maria Sibylla Merian, on her observations in Amsterdam

In 1691, she and her daughters moved to Amsterdam. She was determined to illustrate and explore the natural wonders of tropical habitats.2 She believed that, “If I could study these insects in their natural habitat, I could write a book that people would notice.” 10

A Journey Abroad

“So I was goaded to undertake a huge and costly trip, traveling to Suriname in America, a hot and humid land where swarms of insects are there for the capture……It is very hot in that country, so that one can only work with the greatest difficulty…which is why I could not remain there any longer; also all the people there were amazed that I came out of it alive, for most people there die of the heat.” 7,8-Maria Sibylla Merian, describing Suriname’s conditions

In July 1699, by then a well-known artist-naturalist, she sold most of her possessions, including her paintings, to sail with her younger daughter to the rainforests of Surinam, a place she had dreamed of seeing for more than a decade.2,3,5

She was a woman far ahead of her time, doing something unheard of in that period– traveling such a far distance alone with her daughter and notably, without a male companion.11 For two years, they traveled throughout Surinam keenly studying wildlife, mainly insects and their metamorphosis, that was very different from her prior European observations.2

She observed large tropical butterflies, among other insects, and was even able to observe high canopy species that dwell well out of human view by examining a tree a man cut down for her.2

In June 1701, she fell ill, possibly suffering from malaria, and had to return to Amsterdam.3 She and her daughter managed to bring a hoard of preserved animals and insects with them in their luggage, along with many drawings, which they displayed in their house in Amsterdam.3 She sold specimens for income and for four years worked on finalizing the watercolors and engravings of the many life forms she observed.2

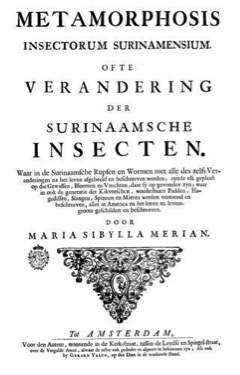

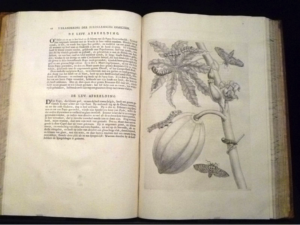

Most of the drawings of tropical flora and fauna were for her most magnificent work, Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium (Transformation of the Suriname Insects). This three-volume book, published in 1705, consisted of watercolor paintings, detailed descriptions, and scientific observations of insects, including butterflies and beetles, and their host plants seen in Suriname.2,3,5,8

These works were accompanied by text detailing the life cycles of insects, and for holometabolous species, descriptions of their complete metamorphosis.2This technique set a precedent for other artists to imitate.12

Merian was focused on painting her subjects with great accuracy and detail, and was careful not to add her own opinion or draw conclusions. She described, “Because the world today is very sensitive and the learned differ in their opinions, I have kept simply to my observations; in so doing [providing] material for each individual to draw his own conclusions according to his own understanding and opinion, which he can then evaluate according to his own judgement.” 7 -Maria Sibylla Merian, from the introduction to Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium

In the introduction to her book, Merian describes one butterfly, most like the iconic Blue Morpho butterfly species, that she found particularly spectacular.

“I found this yellow caterpillar which had pink stripes over its whole body; its head was brown and each segment bore four black spines; its feet were also pink. I took this caterpillar home with me and it rapidly changed into a pale wood-coloured chrysalis…two weeks later, towards the end of January 1700, the most beautiful butterfly emerged, looking like polished silver overlaid with the loveliest ultramarine, green and purple, and indescribably beautiful; its beauty cannot possibly be rendered with the paint brush.” 7

After returning from Surinam, Merian explained how she managed the process of depicting the diverse life she observed. While she painted and described all the larvae and caterpillars and their food in their natural habitats, she also brought back specimens preserved in brandy or pressed for anything she did not have to paint immediately. This allowed her to paint these specimens the way she was accustomed to in Germany, on vellum in large format, so that the creatures were life-size.

The book based on her Suriname observations was a success, although the finances it generated were not enough to support her for the remainder of her life.2 However, Merian preferred scientific knowledge over wealth and comfort, and with her keen sense of observation, she continued to study her beloved insects and lived quite frugally, selling her paintings as a means of support.

In 1715, Merian suffered a stroke, leaving her partly paralyzed. She never fully recovered, passing away on January 13, 1717 in Amsterdam.2

Sexism / Delayed Honors and Legacy

Despite her expertise, as a woman at the dawn of the Age of Enlightenment, Merian was barred from discussions, even when they concerned her own findings.2After her death, certain 19th century English natural scientists openly scorned Merian’s methods and belittled her discoveries.19

Merian used more comprehensive balanced compositions, of flowers like fused tulips, peonies and lilies,in their natural surroundings, including butterflies,caterpillars and insects in the artwork, which were non-traditional illustration modes for the 16th and 17th centuries. The feminist movement of the 20th century widened Merian’s appeal by exhibiting her paintings with those of other neglected female artists.19

While she was not recognized with many awards or honors during her life, Merian is remembered for her legacy of detailed intricate paintings of species in their natural environment.

“Maria Sibylla Merian was certainly one of the finest botanical artists of her time.” 12 -Wilfred Blunt, The Art of Botanical Illustrations, first published in 1950

In 1997, Merian was honored in Frankfurt, her hometown, with an exhibition at the Historisches Museum in celebration of her 350th birthday.19

This exhibit displayed faience (tin-glazed pottery) and porcelain from the mid-eighteenth century onward decorated with Merian’s artwork, as painters of ceramics found inspiration in her floral designs.19

Interest in botanical illustrations resurfaced by decorators and art collectors in the 1970s, and more so, thereafter. In the late 1990s, a floral plate of Maria Sibylla Merian’s sold for $3,800.12

Carl Linnaeus, the scientist credited for formalizing taxonomy, the system in which plants and animals are characterized, used many of Merian’s drawings and descriptions to name species he had never seen. Thirty years after Merian’s death, Linnaeus developed the taxonomic system we still use today.

Linnaeus relied on Merian’s accurate artwork to describe a number of species he never saw, so the names of many animals and plants, such as a Cuban sphinx moth (Erinnyis lassauxii (=merianaeI)), cane toad, snail, lizard, bird-eating spider, a genus of praying mantises, a genus of exotic flowering plants, a bugle lily species, and two sub-species of butterfly (Opsiphanes cassina merianae), reference Merian (merianae).11,13

Her illustrations were so precise that entomologists today are able to identify the genus of 73 percent of the butterflies and moths in Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium, and match 56 percent of the insects to specific species.13

The Soviet Academy of Sciences re-published a book of Merian’s paintings in the mid-1970s, which sparked new interest in and marked a sort of renaissance for her work.

This book of about 300 watercolors was first published shortly after Merian’s death in 1717, when Czar Peter the Great bought the paintings from Merian’s daughter.11

Some of the butterfly specimens prepared by Merian in Suriname have survived for 400 years and can still be seen today, as part of the “Gerning Collection” in the Landesmuseum Wiesbaden in Germany.3

Merian’s Contributions Recognized

In more recent times, Merian has enjoyed recognition for her work, appearing on currency and postage stamps in Germany.

She has also been featured in scholarly journals and museum exhibits, including the exhibit by the The J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles entitled, Maria Sibylla Merian & Daughters: Women of Art and Science in 2008.11

A New Butterfly Species Now Bears Her Name

A new butterfly species was named in honor of Maria Sibylla Merian in December 2018. In a paper introducing the butterfly, Shinichi Nakahara and his colleagues from the Florida Museum of Natural History named the species Catasticta sibyllae.13

While other species have been named in her honor, this is the first time that a full-fledged butterfly species (rather than a subspecies) bears her name.13 In recent years, there have also been numerous prizes and scholarships named in Merian’s honor to support women artists and scientists.

Author’s Tribute

Visit our Gallery to view a series of three watercolor paintings by Varsha Mathrani that were inspired by Maria Sibylla Merian.

Authored by: Varsha Mathrani

References

- Maggs, Sam. Wonder Women: 25 Innovators, Inventors, and Trailblazers Who Changed History. Quirk Books, Philadelphia, 2016.

- Engel, Michael S. Innumerable Insects: The Story of the Most Diverse and Myriad Animals on Earth. Sterling New York, New York, 2018.

- Schumann, Bettina. 13 Women Artists Children Should Know. Prestel Verlag, Munich, 2010.

- Todd, Kim. Chrysalis: Maria Sibylla Merian and the Secrets of Metamorphosis. Harcourt, Inc., Orlando, 2007.

- Weidemann, Christiane, Pretra Larass, and Melanie Klier. 50 Women Artists You Should Know. Prestel Verlag, 2016.

- Swaby, Rachel. Headstrong: 52 Women Who Changed Science– and the World. Broadway Books, 2015.

- Ferguson, Kitty. Lost Science: Astonishing Tales of Forgotten Genius. Sterling, 2017.

- Brafman, David and Stephanie Schrader. Insects & Flowers: The Art of Maria Sibylla Merian. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, 2008.

- Nelson, E. Charles and David J. Elliott. The Curious Mister Catesby: a “truly ingenious” naturalist explores new worlds. The University of Georgia Press, Athens, 2015.

- Favilli, Elena and Francesca Cavallo. Good Night Stories for Rebel Girls: 100 Tales of Extraordinary Women. Timbuktu Labs, 2016.

- The Iris: Behind the Scenes at the Getty. Maria Sibylla Merian, Trailblazing Artist-Scientist of the Seventeenth Century. Retrieved from http://blogs.getty.edu/iris/maria-sibylla-merian-trailblazing-artist-scientist-of-the-seventeenth-century/

- Kramer, Jack. Women of Flowers: A Tribute to Victorian Women Illustrators. Steward, Tabori & Chang, New York, 1996.

- New Butterfly Species Named After 17th-Century Female Naturalist. Retrieved from https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/new-butterfly-species-named-after-17th-century-female-naturalist-180970979/

- Keppler, Utta. Die Falter frau: Maria Sibylla Merian. Eugen Salzer Verlag, Heilbronn, 1997.

- Merian, Maria Sibylla. Das Insektenbuch: Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium. Erste Auflage, Frankfurt am Main and Leipzig, 2002.

- Merian, Maria Sibylla. The Wondrous Transformation of Caterpillars: Fifty engravings selected from Erucarum Ortus (1718). The Scolar Press, London, 1978.

- Dickenson, Victoria. Drawn From Life: Science and Art in the Portrayal of the New World. University of Toronto Press Incorporated, Toronto, 1998.

- Davis, Natalie Zemon. Women on the Margins: Three Seventeeth-Century Lives. President and Fellows of Harvard College, Cambridge, 1995.

- Jacob-Hanson, Charlotte. Maria Sibylla Merian, artist-naturalist. The Magazine Antiques. New York, August 2000.

- Popova, Maria. Art, Science, and Butterfly Metamorphosis: How a 17th-Century Woman Laid the Foundations of Modern Entomology. Retrieved from https://www.brainpickings.org/2013/09/18/maria-sibylla-merian/?mc_cid=ed74d8baec&mc_eid=61e26ae3f3

- Maria Sibylla Merian-Preis. Retrieved from http://www.kulturpreise.de/web/preise_info.php?cPath=9&preisd_id=1950

- Academy Merian Prize. Retrieved from https://www.knaw.nl/en/awards/awards/knaw-merian-prize

- Maria Sibylla Merian-Prize. Retrieved from https://www.uni-due.de/ekfg/prize.shtml

Image Credits

- From Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium, Plate XX. (Thysania agrippina), USA Public Domain https://sv.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fil:Thysania_agrippina_par_Merian.gif

- Colorized Portrait of Merian, 17th century, USA public domain: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Maria_Sibylla_Merian_portrait_colors.jpeg

- Matthäus Merian the Elder, German engraver, USA Public Domain https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:MatthaeusMerian.jpg

- Self-portrait of Jacob Marrel (1613/1614–1681), etching, 1661, USA Public Domain https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jacob_Marrel_Selbstportrait.jpg

- Still life with fruit, a grasshopper and a butterfly, by Maria Sibylla Merian, from 1670-1680, USA Public Domain https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Still_life_with_fruit,_a_grasshopper_and_a_butterfly,_by_Maria_Sibylla_Merian.jpg

- Illustration of Passiflora incarnata by Maria Sibylla Merian from Neues Blumenbuch, 1675, USA Public Domain https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sibylla_merian_passiflora_incarnata_1675.jpg

- Maria Sibylla Merian: Der Raupen wunderbare Verwandelung und sonderbare Blumennahrung [The wondrous transformation of caterpillars and their remarkable diet of flowers], 1679, USA Public Domain https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Datei:Merian_-_Der_Raupen_wunderbare_Verwandelung_und_sonderbare_Blumennahrung_-_1.jpg

- Maria Sibylla Merian: Der Raupen wunderbare Verwandelung und sonderbare Blumennahrung [The wondrous transformation of caterpillars and their remarkable diet of flowers], 1683, USA Public Domain https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Merian_-_Der_Raupen_wunderbare_Verwandelung_und_sonderbare_Blumennahrung_-_2.jpg

- The cover page of the book Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium by Maria Sibylla Merian, published in 1705, USA Public Domain https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Insects_of_Surinam.jpg

- “Verandering der Surinaamsche Insecten” (Amsterdam, 1730) by Maria Sibylla Merian; Rijksmuseum, Creative Commons Attribute: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Maria_Sibylla_Merian_-_Insectenboek_001.JPG

- Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium, hand-colored copper engraving by Merian, 1705, USA Public Domain: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Merian_Metamorphosis_LX.jpg

- Colored Image of Merian, ~1700, USA Public Domain: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Anna_Maria_Sibylla_Merian_portrait_in_color.jpg

- Colored copper engraving from Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium, Plate XLIII. “Spiders, ants and hummingbird on a branch of a guava” (Tarantula: Avicularia avicularia), 1705, USA Public Domain https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Avicularia-avicularia.jpg

- Illustration of a Spectacled Caiman and a False Coral Snake (1701–1705) by Maria Sibylla Merian, watercolor and gloss over etching on parchment, USA Public Domain https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Illustration_of_a_Caiman_crocodilus_and_an_Anilius_scytale_(1701%E2%80%931705)_by_Maria_Sibylla_Merian.jpg

- Metamorphosis of a Frog and Blue Flower by Maria Sibylla Merian. 1701-1705. Watercolor on paper. Source: Minneapolis Institute of Arts (Mia) accession number 66.25.171, 1 January 1701,USA Public Domain.https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Metamorphosis_of_a_Frog_by_Maria_Sibylla_Merian.jpg

- German banknote of the fourth series (since 1989/90), Public Domain. https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Datei:500_DM_Serie4_Vorderseite.jpg

- Exhibition of the Natural History Collections of the Museum Wiesbaden, 17 January 2018, Creative Commons License. https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Datei:Museum_Wiesbaden_Merian.jpg